Mahler Online CoursePart 2 – Mahler’s Biography

by Bettie Jo Basinger

Gustav Mahler

On 7 July 1860, Gustav Mahler was born into a middle-class Jewish family living in Kalischt, a town within the Hapsburg Empire (now Kaliště in the Czech Republic). Although his parents had a total of fourteen children, Mahler became the oldest child of the six that would survive infancy. He grew up in Iglau (now Jihlava in the Czech Republich)—where his parents moved before the end of his birth year—as a German-speaking Jew within a culturally Czech community.

The primary and second schools of Iglau did not offer much in the way of musical training. Mahler nevertheless began playing the family piano at a very young age, and by the time he reached ten, many considered him a local prodigy. The music director of a nearby church—and father to one of the future composer’s boyhood friends—gave Mahler his first music lessons. In addition, the composer learned by studying the scores of past masterpieces loaned to him by libraries and teachers, as well as by absorbing the Czech and German musical traditions heard throughout the town.

At the start of the 1875-1876 academic year, Mahler entered the conservatory in Vienna, and this commenced his formal musical education. He continued to study piano at this institution, yet composition attracted more and more of his attention. His pieces earned several awards, but never the coveted Beethoven Prize which Mahler sought twice, submitting his overture for a projected opera called Die Argonauten (The Argonauts, now lost) in 1878 and the cantata Das klagende Lied (The Song of Lamentation, 1878-1880; revised 1892-1893, 1898-199) in 1881.

Before leaving the conservatory, Mahler began attending lectures at the University of Vienna. He chose to pursue topics in philosophy, literature, European history, art history, and music history; those in harmony (delivered by Anton Bruckner) nonetheless interested Mahler most. At this same time, the burgeoning composer also began giving piano lessons, and he gained conducting experience by leading student rehearsals.

This image of Mahler probably captured him around the age of five or six. The name of the photographer remains unknown.

His participation in the latter led to several short-term appointments as a conductor of operetta and opera in Bad Hall, Laibach (now Ljubljana in the Republic of Slovenia), and Olmütz (now Olomouc in the Czech Republic) between 1880 and 1883. While none of these constituted prestigious positions, Mahler’s years of working in second- and third-tier theaters established the 23-year old as a vibrant and innovative conductor. Thus, he was able to accept a more prestigious position in Kassel as second conductor under Wilhelm Trieber during August of 1883. In addition, Mahler’s years in Kassel saw the composition of incidental music for Joseph Victor von Scheffel’s play Der Trompeter von Säkkingen (The Trumpeter from Säkkingen, 1884) and the song cycle Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer, 1883-1885; revised 1891-1896).

In April of 1885, Mahler left Kassel having already accepted a conducting position in Leipzig. However, this new appointment did not begin until 1886. Fortunately, Prague offered a temporary stopgap at the Neues Deutsches Theater (New German Theater). As this house’s second conductor, Mahler helped revitalize the quality of its productions and attendance, the latter of which was suffering due to the Czech National Theater’s decision to program works by Czech and Russian composers in an effort to cater to the nationalism of Prague’s Czech-speaking audience.

Yet by July of 1886, Mahler had arrived in Leipzig to take up his post at the Neues Stadttheater (New City Theater). Once again, he held the position of second conductor; here he operated beneath the celebrated maestro Arthur Nikisch, and the two conductors acted as bitter rivals. Tensions increased as Mahler became involved with the Weber family, both by completing Carl Maria von Weber’s unfinished comic opera Die drei Pintos (The Three Pintos) in 1887, as well as becoming romantically attached to the wife of Weber’s grandson. Following a public disagreement with the Stadttheater’s stage manager, he therefore resigned.

Mahler next relocated to Budapest in order to assume directorship of the Royal Hungarian Opera in 1888. Tragedy marred the beginning of the composer’s tenure in this city, since his father, mother, and one of his sisters all died in 1889. But he premiered some significant works in the Hungarian capital, including the initial version of his First Symphony (1884-1888; revised 1893-1896, 1906) on 20 November 1889, as well as several of the piano-vocal songs that he would publish under the collective title Lieder und Gesänge (Songs and Chants, 1880-1890) on 13 November of the same year. Like Prague, though, politics impacted Mahler’s duties in Budapest, and when Count Géza Zichy, a Magyar nationalist and anti-Semite, became the intendant of the Royal Opera, the composer began seeking his fortunes elsewhere.

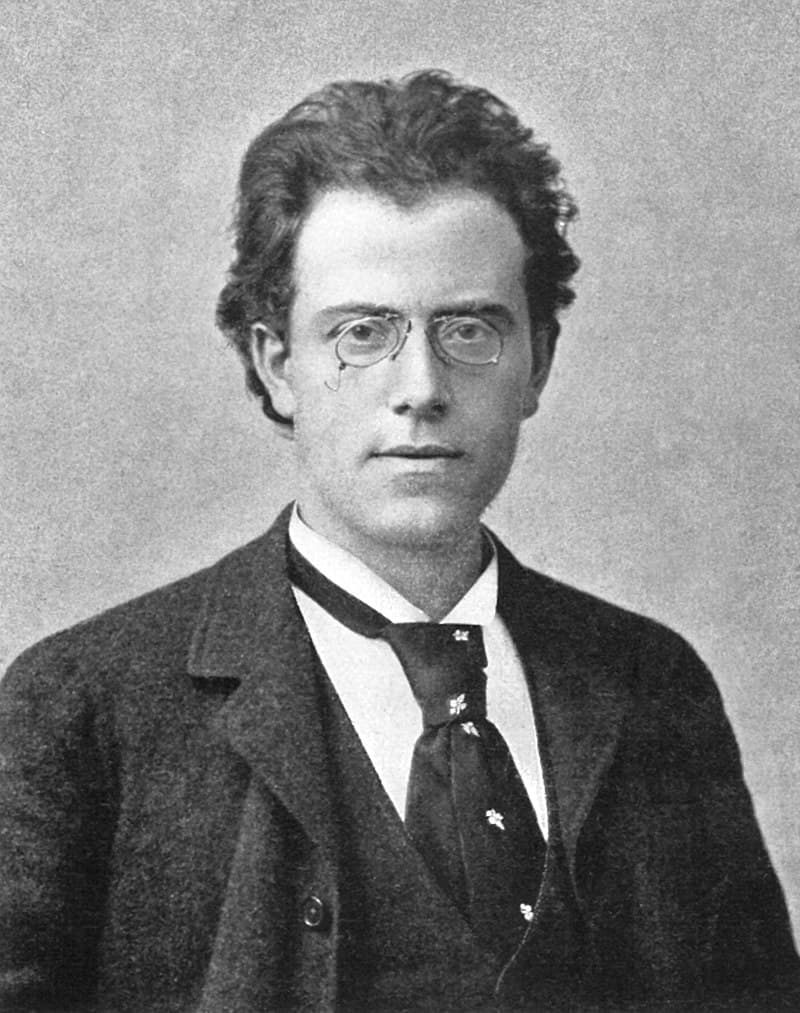

Emil Bieber took this photograph of Mahler around 1892. Adolph Kohut incorporated the image in his entry on the composer in the first volume of Berühmte israelitische Männer und Frauen in der Kulturgeschichte der Menschheit (Famous Jewish Men and Women in the History of Civilization) of 1900.

After resigning from his position in Budapest during March of 1891, Mahler immediately became chief conductor at the Hamburg Stadttheater (City Theater). This city witnessed the completion of his Second Symphony (1888-1894; revised 1903), several of the songs of Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy’s Magic Horn, 1892-1898), and the Third Symphony (1893-1896; revised 1906). Moreover, though his appointment theoretically encompassed directing operatic works, the death of the orchestral conductor Hans von Bülow in 1894 allowed Mahler to take over more of the city’s instrumental performances. Unfortunately, his approach to this task may have contributed to Hamburg’s decision not to renew his contract after 1897: Mahler took liberties with the instrumentation and tempos of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (1822-24) during a performance of the 1894-1895 season that caused a stir and resulted in a drop in ticket sales.

Because Mahler had converted to Catholicism on 23 February 1897, he had removed a barrier blocking his appointment to Imperial positions in Vienna (which Jews could not hold). In April of 1897, the composer became Kapellmeister (Court Music Director) in this city, and by 8 September, he received a promotion to director of the Court Opera (now the Austrian State Opera). By the fall of 1898, Mahler had accepted an additional posting as the conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic, which he held for three seasons that again aroused controversy due to his tendency to alter the instrumentation and dynamic contrasts of great compositions of the past.

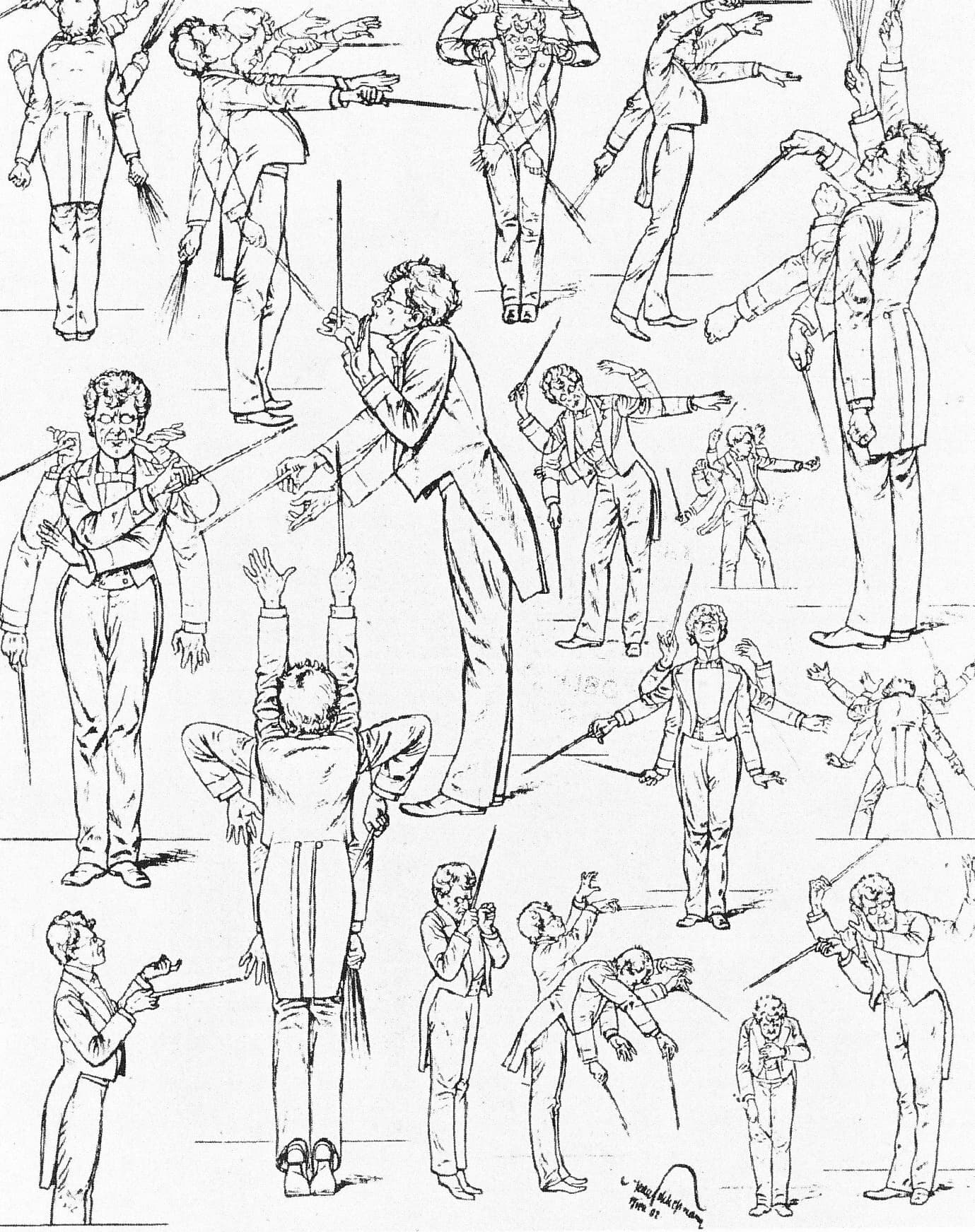

This cariacture of Mahler’s conducting style by Hans Schliessmann first appeared in the Germa magazine Fliegende Blätter in 1901.

Meanwhile, the composer’s personal life underwent tremendous change during his time in Vienna. He married Alma Schindler, twenty years his junior, on 9 March 1902, and the couple had two daughters, Maria and Anna, born 3 November 1902 and 15 June 1904 respectively. These years also proved extraordinarily productive compositionally, with Mahler completing his Fourth (1892, 1899-1900; revised 1901-1910) Fifth (1901-1902) Sixth (1903-1904; revised 1906), Seventh (1904-1905), and Eighth (1906-1907) Symphonies while employed by this city. The orchestral song cycle Kindertotenlieder (Songs on the Death of Children, 1901-1904) also dates from this time.

As Mahler generated these new works, however, he began to take short trips away from the Austrian capital in order to conduct his symphonies in other European locations. Although he still took an active interest in all productions at the Vienna Court Opera, his outside activities began to anger court officials during the 1906-1907 season. Meanwhile, the anti-Semitic press used any misunderstanding between the theater’s musicians and Mahler—who always made high demands of both the singers and instrumentalists under his baton, and he frequently came off as rather insensitive to the feelings of individual performers while conducting—to fuel their vitriol against him. The composer consequently signed a contract with New York’s Metropolitan Opera house.

Yet before the family could leave the European continent, the children contracted scarlet fever. Anna recovered, but Maria succumbed to a combination of this infection and diphtheria on 12 July 1907. Having lost so many siblings in their infancy, the composer took the death of his five-year old daughter particularly hard, and as if to compound his pain, a routine examination by Maria’s attending physician revealed that Mahler himself had valvular heart disease.

Regardless of these personal catastrophes, in 1908 Mahler became one of the many European artists recruited by New York to satiate the city’s desire for cultural prestige. Despite the high salary of his position, the composer felt dismayed by the conservative musical choices of the Metropolitan Opera. Fortunately, relief came in his second season with further conducting opportunities offered by the New York Symphony Orchestra and, by 1909, the newly reformed New York Philharmonic.

Alma and Mahler always returned to Europe for the summers, and during these off-seasons, he did most of his composition (a habit of Mahler’s since 1893) in between continental conducting engagements. Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth, 1908-1909), the Ninth Symphony, and the unfinished Tenth Symphony (1910) all date from this time period. In February 1911, though, Mahler fell ill in New York. At first, he thought his sickness was resulting from the tension developing between the Philharmonic, its financial backers, and himself; it nevertheless soon became clear that the composer had contracted bacterial endocarditis. The Mahlers therefore returned to Vienna, where Mahler died on 18 May 1911.

Despite Mahler’s promotion of his own music through his efforts as a conductor, his output remained relatively unknown at the time of his death. His repertoire would languish further during the time of Hitler, due to Austro-German attitudes about Jewish artists and their works. But around 1960, Leonard Berstein, then at the helm of the New York Philharmonic, triggered reevaluation of Mahler by performing, recording, and championing the composer’s works. Other conductors and scholars in the United States and England soon followed suit, including Maurice Abravanel and the Utah Symphony Orchestra. This ensemble, under Abravanel, holds the distinction of releasing the first recording of the complete cycle of Mahler symphonies by a single group.

About the Author

Bettie Jo Basinger has been teaching at the University of Utah since 2007. She has both a Master’s Degree and PhD in Musicology—as well as a Bachelor’s in French Horn Performance—from UCLA. Although her research interests include the entire symphonic repertoire, Dr. Basinger specializes in the orchestral program music of the nineteenth century, particularly the symphonic poems of Franz Liszt.