HAYDN: Symphony No. 11

by Jeff Counts

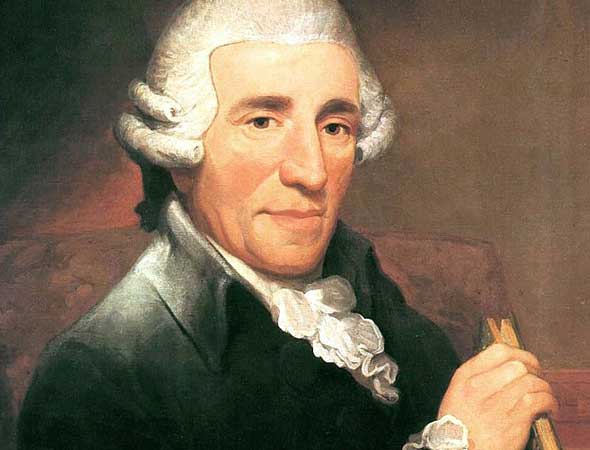

THE COMPOSER – FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN (1732–1809) – In 1761, Haydn left his post with Count Ferdinand Maximilian von Morzin of Bohemia to assume the vice-Kapellmeistership at Eisenstadt for Prince Pál Antal Esterházy. The timing couldn’t have been better. Morzin’s court was in financial distress at the time, forcing the orchestra to be disbanded. Prince Esterházy certainly saw something important in the young composer’s Morzin-period works, especially the five symphonies that began Haydn’s epic, lifelong devotion to the genre. It would turn out to be the most significant patronage of the composer’s life (not to mention an immeasurable gift to the future of music history), and Haydn nurtured the relationship dutifully until his death.

THE HISTORY – It isn’t completely clear if Haydn’s Symphony No. 11 was a Morzin piece or an Esterházy piece. Written sometime between 1760 and 1762, this work embodies Haydn’s professional transition in an interesting way. Designed quite possibly as a companion piece for Symphony No. 5, No. 11 was also built on the model of an Italian Sonata da chiesa or “church sonata.” That form boasts a four-movement, roughly slow-fast-slow-fast plan that frequently relies on a juxtaposition of binary frameworks and long monothematic statements. Though he had toyed with the idea of four movements (as opposed to three) a few times by this point, it would not become standard practice for Haydn for another several years. Also worth mentioning is the slow opening movement, an idea that would remain a sporadic novelty throughout his symphony-writing career. In 2016, London-based Classic FM asked one of their staff writers to listen to, as consecutively as possible over several days, all 104 of Haydn’s symphonic treasures and rank them from worst to first. It’s a feat of concentration no one should attempt to repeat, but the challenge resulted in a highly interesting document, even if it is only one person’s exhausted opinion. Hidden among the barely contained madness of his efforts were some observational gems, like how the rare slow first movements in Haydn symphonies fall into two camps—“spectral beauty” or “meandering plod.” Ouch. At least Symphony No. 11 (which he awarded with a top ten spot) is from the former group with its “interlocking lines of melody that wind around each other most attractively.” Additionally, he was struck by the Menuet, which includes an “impish trick” that delays the accompanying material by one beat for certain instruments, giving the Trio section a deliberately “clumsy” feeling. As numbers go, 11 is a long way from 104, but clearly Haydn was never anything but himself. The signature wit and creative spark that define him now were with him from the earliest days.

THE WORLD – Elsewhere in 1762, the Seven Years’ War raged in Europe, Empress Elisabeth’s death in Russia made way for Catherine the Great, and New York had its first St. Patrick’s Day Parade.

THE CONNECTION – Though they regularly perform Haydn Symphonies on the Masterworks Series, these concerts represent the Utah Symphony premiere of No. 11.