BERLIOZ – Symphonie fantastique, Op. 14

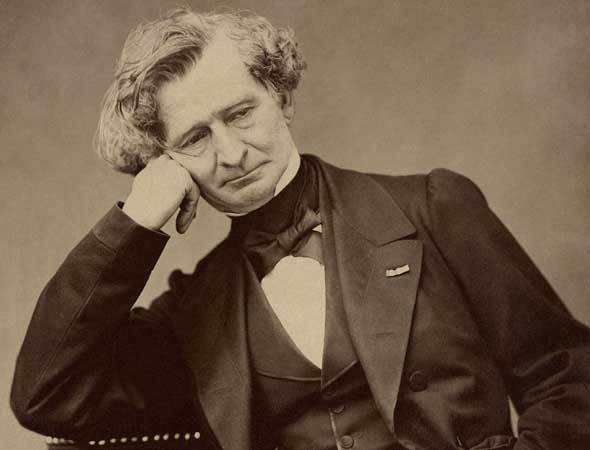

Hector Berlioz

- Reveries and Passions: Largo – Allegro agitato e appassionato assai

- A Ball: Waltz – Allegro non troppo

- In the Country: Adagio

- March to the Scaffold: Allegretto non troppo

- Dream of the Witches’ Sabbath: Larghetto – Allegro

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR IN SYMPHONIE FANTASTIQUE

We can listen to the movements as if they were chapters in an artist’s life. They begin with his idle dreams and passionate thoughts, then meander through a series of intricate modulations. In their midst he glimpses his romantic ideal, and we are introduced to the yearning motif of the idée fixe. The second movement, glittering with elegance, is titled simply “Un bal”—a ball. A gorgeously alluring waltz swirls through the movement, but the beloved seems tantalizingly out of reach. As the movement progresses, the sensuality of dancing merges with the breathlessness of pursuit. The artist’s quickening steps are never quite fast enough. Berlioz described the third movement as an evening in the countryside during which the artist broods on his loneliness. It is slow and melancholy, with the artist musing on the faithlessness of a beloved who is not even his to begin with. Amid the silence, we hear ominous hints of distant thunder. In the fourth movement the artist, unable to bear his loneliness, attempts to poison himself with opium. But instead of dying, he is plunged into a fever-dream in which he has killed his beloved and is condemned to death by hanging. With its nightmarish “march to the scaffold,” this movement is one of the most famous passages in Berlioz’ catalog. And it may well be a case of life imitating art: It was composed during the period when Berlioz himself was taking opium, and he is said to have written it like a man possessed, finishing it in a single night. In the fifth movement, the artist’s downward slide reaches its end—not with his death, but with his funeral, a witches’ sabbath evoking demons and monsters of all sorts. The mood is jubilant yet ghoulish, like a diabolical orgy incorporating (shockingly, for observant Catholics of Berlioz’ era) parodies of the Dies irae chant as well as the idée fixe. The love story is complete.