SCHOENBERG: Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night)

When did the “modern” era in classical music begin? Improbable as it seems, it’s possible to trace the onset of musical modernism to a single man and a single musical work: Arnold Schoenberg, whose tone poem Verklärte Nacht, or “Transfigured Night” seemed to take the complexities of Late Romantic harmonic theory to their ultimate extreme.

Both a composition of shimmering beauty and a fascinating exploration of a human psyche in flux, Transfigured Night hardly seems threatening. Yet it evoked controversy and terror among the musical partisans in Schoenberg’s native Vienna, who considered the history of European classical music—especially the symphonists descended from Beethoven through Brahms and Mahler—to be their personal patrimony. Transfigured Night, with its artful extremes of harmony, seemed to take the linear progression of music theory, which depended upon techniques of harmonic modulation that had evolved for centuries, as far as they could go. What remained for Late Romanticism? And what could possibly lie beyond it?

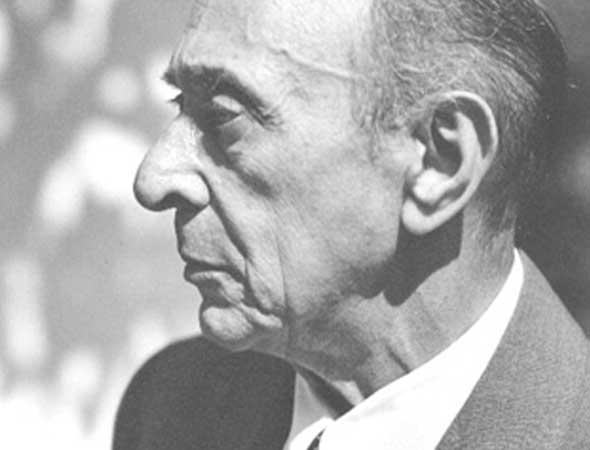

Arnold Schoenberg

As the seminal figure of the “Second Viennese School,” Schoenberg developed the compositional framework that became associated with terms such as “serial music,” “twelve-tone,” and “atonality.” Though we do not hear these techniques in Transfigured Night, traditionalists knew that this 1899 tone poem for string sextet led to the brink of atonality; beyond it lay a new kind of sound and a new way of listening—and the end of centuries of evolutionary development in compositional technique. Ravishingly sensual, yes, and harmonically rich; yet somehow this composition, with its deeply modern (Freudian) subject matter, marked the ultimate boundary for traditional composition. A decade later, Schoenberg would publish his encyclopedic Harmonielehre (1910), the text that provided the theoretical basis for twelve-tone composition. Transfigured Night was Schoenberg’s first major composition, but the last that would locate him in the late romantic tradition of Brahms, Wagner, and Richard Strauss. Beyond that lay the modernity of atonal composition and the tutelage of Schoenberg’s compositional mentor, Alexander Zemlinsky.

Born in 1874, Schoenberg composed in the intellectual hothouse that was turn-of-the-century Vienna. Early in his career, in compositions such as Transfigured Night, he explored ways of extending the romantic styles of Wagner and Brahms, who were considered antagonists by their contemporaries. But in fin-de-siècle Vienna there was a sense that more than just the century was ending; to many thinkers, traditional ideas about art and music seemed headed for a dead end. Schoenberg’s controversial new compositional method replaced traditional scales with the entire chromatic scale, unanchored by any particular “home” tone, and not reliant upon familiar intervals or harmonies. His groundbreaking ideas, which inspired passionate advocacy and opposition, still strike fear into some listeners…at least by reputation. The fact is, we all take more extreme musical styles in stride when we hear them in today’s movies and television shows.

Listening to Transfigured Night, we might never guess that such musical innovations were in the offing. Schoenberg used the string sextet form to create a sense of fecundity and the shimmering textures of a moonlit forest. He rescored the work a number of times, and it has challenged other arrangers as well. Schoenberg took inspiration for the work from a poem by the Austrian poet Richard Dehmel—a love poem with an intensely psychological narrative line taken from the collection Weib und Welt (“Woman and World”). The chill of the poetic scenario’s night air and the tension of physical intimacy between man and woman are evident from the music’s opening bars, and though the text is not included in Schoenberg’s composition, it is in direct accord with Dehmel’s poem, beginning with the woman’s anguished confession to her lover that she is pregnant by another man. In pursuing what she thought was her only chance at happiness—motherhood—she feels that now, having met her true love, fate is punishing her.

With her confession, the man and woman embark on a journey of transfiguration that takes them through the darkness of the forest in five uninterrupted movements. The man’s initial consoling response to his lover’s words is reflected in mellow, deep-toned lines that are followed by a rapturous love duet. The transition from guilt through forgiveness brings them to an ecstatic union that goes beyond the physical impulse of love to something deeper: their love, the man assures her, will make the child his. Both lovers are transfigured through the night of communion they share—as is the unborn child they look forward to raising together.

The complex, chromatic harmonies and mercurial lines we hear in Transfigured Night are characteristic of the tone poems popularized by Liszt and Richard Strauss—especially Strauss, whose mastery of dense, iridescent harmonies and sensual effects prefigured Schoenberg’s. As we listen, the line of Schoenberg’s narrative forms a perfect arch: from the poem’s opening line, “Two people walk through a bare, cold wood;” to the last, “Two people walk on through the high, bright night.”

The author of those lines, Richard Dehmel, was in attendance at the premiere of Transfigured Night in Vienna. “I had intended to follow the [movement] of my text in your composition,” he later told Schoenberg. “But I soon forgot to do so, I was so enthralled by the music.”