BEETHOVEN: Symphony No 3 “Eroica”

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons; 3 horns, 2 trumpets; strings; percussion.

Haydn wrote 104 symphonies. Mozart, who died when he was only 35, wrote 41. Yet Beethoven’s ninth symphony was his last. After that, the form seemed more formidable, and the idea of composing dozens of symphonies in one lifetime passed into history. Composers began to think of the number nine as an upper limit for symphony composition, or even a jinx. Clearly, Beethoven had done something to change the way the music world thought about symphonies. What was it?

If one symphony can be called a turning point in the way Beethoven and the world viewed the form, it is the Eroica. Where Beethoven’s first two symphonies are graceful and decorously Classical, with the influence of Haydn and Mozart clearly heard, the Symphony No. 3 is a bold musical utterance that is longer in duration and bolder in its ideas than were its predecessors – literally a “Sinfonia Eroica,” or heroic symphony.

But this title, which Beethoven himself appended to the symphony, was a last-minute revision of his original idea. Always concerned with the important ideas and events of his time, Beethoven had Napoleon Bonaparte in mind as the hero of this work. Like many intellectuals who opposed the oppressive regimes of central Europe, Beethoven saw Bonaparte as a potential savior. As early as 1798, Beethoven considered writing a symphony inspired by Napoleon. Significantly, he composed much of the music for it during the summer of 1803, the year after he wrote the Heiligenstadt Testament — the unsent letter to his brothers that revealed the depths of his feelings about his life, art, and encroaching deafness. In our modern understanding of Beethoven’s lifetime of achievement, the Heiligenstadt Testament marks his transition from a young Classical composer to a unique musical mind grappling with ideas in a way no composer had done before.

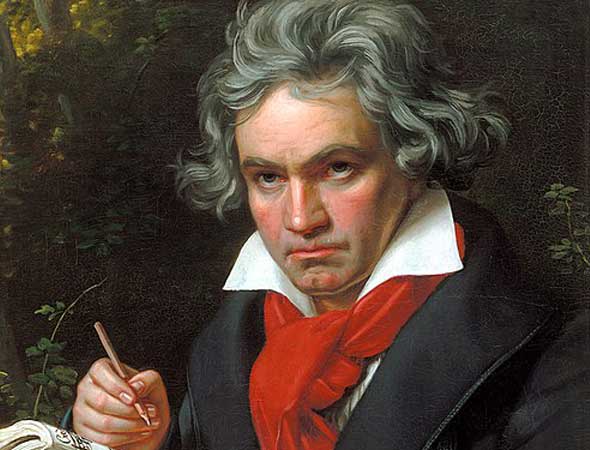

Ludwig van Beethoven

When Bonaparte declared himself emperor, Beethoven viewed his gesture as a denial of the very ideals he saw as heroic — the spirit of equality, brotherhood and freedom we would later hear enshrined in the Choral Symphony. According to one popular account circulated by Beethoven’s student Ferdinand Ries, the composer dramatically “undedicated” the Symphony No. 3, tearing Bonaparte’s name from the score, and what might have been the Sinfonia Bonaparte became the Sinfonia Eroica.

But as the eminent music historian Phillip Huscher points out, Beethoven himself was not entirely beyond personal politics; his decision to drop Bonaparte’s name from the score quickly followed his learning that Prince Lobkovitz would pay him generously for the honor. Later, after the dedication page had been destroyed, Beethoven temporarily changed his mind once again, understanding that a Sonfonia Bonaparte might augur well on his planned trip to Paris. Either way, this idea for a symphony was something new. Other composers were beginning to find ways of incorporating ideas and happenings in their music, but not like this. Beethoven had produced a symphony that was not merely abstract and decorative, but bound up in philosophical ideas and world events, with suggestions of theatrical narrative and the concerns of oratorio.

The Eroica Symphony received its premiere performance in December 1804 in a private concert at the home of Prince Lobkowitz in Vienna. It was brought before the public at Vienna’s Theater an der Wien in April 1805.

With stentorian E-flat chords rumbling through the orchestra, the Eroica Symphony opens onto the largest orchestral movement composed up to that time. And though in those hugely scaled opening moments we don’t know how long the movement may last, the symphony already sounds “big” in its beginnings. These sonic blasts are followed by cello voices that suggest a main theme. But does this movement really have a “main theme” at all? The musical phrases we hear seem more concerned with movement and with a sense of tension, and is through these means that the symphony builds a feeling of fateful importance within us.

In the slow movement that follows, the sense of building tension continues, as if the symphony were brooding over the events of history as they take shape. This movement has come to be known as a funeral march; the critic Paul Bekker, for one, described it as conveying “the emotions of someone watching the funeral procession from afar, passing by, and then fading in the distance.” But this is a halting rhythm – slow, yes, but not conducive to marching. Its solemnity seems to freeze and overwhelm us. Do we hear the sound of mourning for the past, or does the movement point us toward a dark, challenging future? This is one of the first symphonic movements whose slowness and gravity send a hush through the concert hall, and it remains one of the most seriously affecting movements in music. It is accorded a special reverence among musicians. Tellingly, when the news of George Szell’s death reached Leonard Bernstein at Tanglewood in July 1970, Bernstein led the players of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in an unscheduled, emotion-charged performance of this movement in tribute to the Hungarian-born conductor. Reportedly, there were not enough scores to go around — but the players did not need them.

With the third movement, the shape of the symphony begins to emerge as an Orphic struggle through darkness and toward light. It begins with surprising softness opening onto a trio dominated by horns. The effect refreshes us and provides a sense of hope. And it propels us toward a fourth movement that surges with triumphant energy.

Listeners who know their Beethoven are more than familiar with the melody that dominates the fourth movement of the Eroica; it is also heard in his ballet The Creatures of Prometheus and in the piano variations of Opus 33. But when framed for the ballet, this melody is just a catchy, danceable tune, cheerful and lyrical. In the Eroica it is something much more: an expression of apotheosis, joyful and heroic. Many listeners have described this movement as the awakening of a sleeping giant, but surely it is the symphony’s hero rising up. As the movement takes shape into a triumphant march, we can imagine the hero marching into a historic destiny as the symphony’s finale blazes with light.