In Search of Candide

By Michael Clive

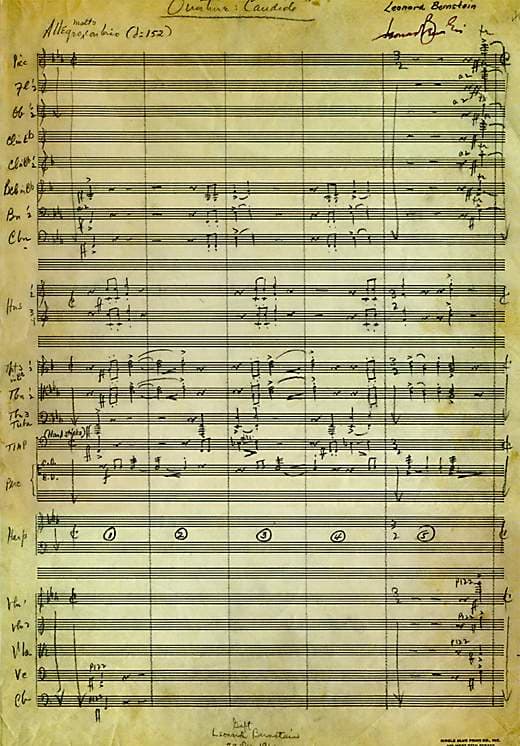

Is this the best of all possible musical comedies in the best of all possible worlds? Well, your annotator is among those who proclaim that Candide is, at the very least, Leonard Bernstein’s greatest score for the stage. It is unquestionably his wittiest—bursting with energy, stylistic panache, and sophisticated, provocative humor. In Candide, the message is in the notes as well as the words: Prepare to laugh and to think.

Why, then, have productions of Candide been dogged by controversy and arguments over authenticity? One reason may lie with another of its superlatives: It has one of the strangest and most convoluted performance histories in the annals of theater. Scholars have lost count of its various performing editions, and even categorizing it spurs arguments: Is it an opera? A Broadway-style musical comedy? Or, as Lillian Hellman and Leonard Bernstein originally called it, a “comic operetta”?

Like the story of Candide the man, the story of Candide the show is an odyssey. We can put it into context by considering two names you might not readily associate with Bernstein: Menotti and McCarthy. The red-baiting witch hunts of Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee were at their worst in 1953, the year when the playwright Lillian Hellman proposed the idea of a musical play based on Voltaire’s Candide to Bernstein. In Voltaire’s satirical 1759 novella Candide, subtitled “The Optimist,” the credulous Candide comes under the influence of Dr. Pangloss, who believes that everything that happens—vile crimes, government atrocities, natural disasters—happens for the best in this best of all possible worlds. Outraged by McCarthy’s “Washington Witch Trials,” which invented communist threats around every corner—and which ruined lives and careers without evidence or due process—Hellman envisioned a musical satire that would critique McCarthyites as Voltaire critiqued church and state in his own times: unmistakably, but without “naming names.”

The idea was irreducibly allegorical, brainy and literary. In 2018, the idea of finding a home on Broadway for this brand of protest-opera might raise eyebrows. But in 1953 it did not, thanks in large measure to Gian Carlo Menotti. Born in 1911 in Italy, Menotti had already written two operas by age 13. He arrived in the U.S. in 1928 at age 17 for studies at the Curtis Institute, and within eight years had a hit, Amelia Goes to the Ball, on stage at the Metropolitan Opera. Before long, he was bringing opera to Broadway, radio and television. The success of Amelia Goes to the Ball brought a commission from NBC for a radio opera for which Menotti wrote his first English-language libretto, The Old Maid and the Thief. Next came The Medium, a dark melodrama he paired with a light one-act comedy, The Telephone, for a successful run on Broadway during the 1947-48 season. Christmas Eve of 1951 marked the first broadcast of Amahl and the Night Visitors, the first opera created expressly for television; with an estimated 5 million people watching, it became the most widely seen opera in history. Menotti followed Amahl in 1954 with the ambitious three-act The Saint of Bleecker Street, which confronted religious, philosophical and social themes, and had a successful Broadway run.

Menotti’s success should have augured well for public acceptance of Bernstein’s category-defying Candide as popular entertainment. It didn’t, despite an assemblage of talent that was almost staggering: In addition to music by Leonard Bernstein and book by Lillian Hellman, it drew contributions by the writers James Agee, John LaTouche, and Algonquin Roundtable wit Dorothy Parker; lyrics by the eminent American poet Richard Wilbur; and musical arrangements by Hershy Kay. Even Bernstein’s wife, the accomplished actress Felicia Montealegro, contributed lyrics. We can’t know what this starry group’s creative process was like, but we can be sure that they argued on their way to Broadway. Menotti, by contrast, was a one-man composer-librettist-director who never doubted himself.

Lillian Hellman’s original conception for Candide was for a play with incidental music, a form similar to her 1952 collaboration with Bernstein called The Lark. The Candide team expanded that idea beyond recognition. And they went further—surely against her wishes—by toning down the acidly written auto-da-fe scene she had framed as an indictment of the infamous McCarthy hearings. By opening night on December 1, 1956, Candide was a work of compromise: an opera designed by committee.

Recalling that brief run more than fifty years later, Barbara Cook, who created the role of Cunegonde, described many of the reviews as “ecstatic,” and they were—about the music and its execution. But audience reaction to the story of Candide and Cunegonde was a resounding “meh.” The influential New York Times called Hellman’s libretto heavy-handed and unironic in its treatment of political themes. And audiences were unsure what to make of the meandering story that enfolded them. It was a picaresque tale like Tom Jones, without the sex but with a brilliant musical score.

The original production of Candide closed after 73 performances at Broadway’s Martin Beck Theatre. Almost as quickly, a legend began to spring up around the show, and having seen Candide became a badge of status that theatergoers boasted and lied about. And so began a succession of revisions and revivals in search of a masterpiece that, if not lost, was hidden: Less than a year after its closing on Broadway, the New York Philharmonic presented a concert version of Candide. For a 1973 revival at the Broadway Theatre, Stephen Sondheim was brought in for additional lyrics and Lillian Hellman’s book was reworked by Hugh Wheeler, the successful British screenwriter, librettist, poet and translator—after which Hellman renounced her association with the show. But the 1973 revival, if less problematic, was also abridged and somewhat denatured. In subsequent revivals, production teams worked to recapture Candide’s original scope in expanded performing editions. Notable productions were mounted in 1982 at New York City Opera, in 1988 at the Scottish Opera, and in 2004 and 2005 at the New York Philharmonic. And the beat went on in Paris (2006), New York (2008), Chicago (2010), London (2013), and elsewhere. Centennial celebrations honoring Bernstein have produced a flurry of revivals in 2017 and 2018 throughout the U.S.

If there is one through-line in the tangled history of Candide, it is the heroic persistence of the important American conductor John Mauceri, who has championed the score and led major revivals. Mauceri, a protégé of Bernstein’s, has not only edited sensitive performing editions of Candide, but also prevailed upon Bernstein to revisit the score himself following Mauceri’s 1988 revival with the Scottish Opera. Bernstein’s 1989 audio and video concert versions of his revision are among the last recorded performances he ever made. They are musically superb and ideally cast, with June Anderson, Jerry Hadley and Christa Ludwig in leading roles.

Does this mean we finally have a definitive performing edition of Candide? In a word, no. Instead, we have a brilliant work of musical comedy that will probably continue to look new and different every time it is produced. That aligns it with the performance tradition of satirical operettas by such masters as Gilbert & Sullivan and Jacques Offenbach, who intended productions to reflect the news of the day whenever they are performed. We can give the last word to music critic Richard S. Ginell, who had the opportunity to see two different Candides in two consecutive weeks earlier this year. Both were in California, but that was about all they had in common. Writing in Classical Voice of North America, Ginell praised both productions and applauded their differences. “Will the dilemma of which version of Leonard Bernstein’s Candide to choose ever be resolved?” he asked. “It doesn’t look like it.”

We’ve Got Those Low-Down, High-Up, Laugh-Out-Loud Coloratura Blues

The tenor gets the title role in Candide, but the soprano gets the most famous aria: “Glitter and Be Gay,” the coloratura showpiece that has become a favorite in auditions and recitals by singers with the skill and daring to get through it. “Glitter and Be Gay” requires everything and then some: faultless coloratura technique; a large vocal range, from chesty low notes to three stratospheric high E-flats; and assured comedic chops. In describing her work creating the role of Cunegonde, the late Barbara Cook compared learning the aria to athletic training. At first, she couldn’t make it all the way from beginning to end. She had all the notes and all the phrasing, but it was simply too exhausting to finish. Eventually she sang it eight times a week, including twice on Wednesdays.

Musically, “Glitter and Be Gay” is a delicious parody that spoofs the highly ornamented arias in the coloratura tradition. These showpieces, with their elaborate runs, trills and arpeggios, prompted Beverly Sills to observe that coloratura sopranos would be a lot richer if they were paid by the note. Bernstein’s take is highly original, but he also winks knowingly at the composers who wrote earlier coloratura parodies.

In this tradition, Cunegonde’s closest sister from another mister may be Rosalinde von Eisenstein, the “respectable wife” in the Viennese operetta Die Fledermaus, by Johann Strauss, Jr. Both Rosalinde and Cunegonde sing of their misery until they can no longer conceal their glee. “How sad I am,” Rosalinde tells her husband, who will spend eight days away from her in jail, leaving her free to flirt with an ex-lover. Like Cunegonde, she expresses her woe in sobbing low phrases that give way to flights of joyous, high-flying coloratura. In “Glitter and Be Gay” Bernstein outdoes the Waltz King, virtuosically turning Cunegonde’s mood around on a single note: Listen for the second syllable of the word “assuage” in the aria’s opening lament.

A century earlier, when Mozart composed two show-stopping arias for the Queen of the Night in The Magic Flute, he knowingly created music that was beautiful yet parodic, and even a tad ridiculous. Sung by a ferocious character, they are ferociously difficult, dramatizing the star-blazing queen’s fearsomeness with notes that seem to stab the air with staccato arpeggios that climb to a high F-natural. In these arias’ extreme vocal demands, Mozart—who advocated simplicity and depth of characterization in opera—put forth an implied critique of vocal display for its own sake.

Like Mozart, whom he venerated, Richard Strauss saw the ridiculous side of coloratura excesses, and in Ariadne auf Naxos he composed another coloratura-aria-to-end-all-coloratura-arias. In it, the burlesque troupe soubrette Zerbinetta addresses herself to the lovelorn, aristocratic Ariadne, whose virtue she suspects to be a bit too severe for the real world. By way of advice, Zerbinetta recounts her own romantic disappointments in what turns into a crazed accounting of endless, heedless promiscuity. The music climbs in labyrinthine chromatic spirals until Zerbinetta collapses from the sheer fatigue of remembering it all.

Of course, the core of the coloratura repertory is bel canto opera, with its mad scenes and lesson scenes. While mad scenes gave composers and their sopranos a chance to use vocal ornament for dramatic effect, lesson scenes were inserted for sheer display, occasioned by the vocal lessons that were common among young ladies of refinement. As Jane Austen’s Caroline Bingley notes in Pride and Prejudice, “A woman must have a thorough knowledge of music, singing, drawing, dancing, all the modern languages” to be considered “accomplished.” Accordingly, the singing teacher is a regular visitor in bel canto drawing rooms, and the soprano’s “voice lesson” may include any showpiece of her choice. A prime example occurs in Rossini’s The Barber of Seville: After Rosina performs for her voice teacher, he responds with “quella voce,” “what a voice”—a line that brings knowing laughter from listeners.

Perhaps the most galvanic lesson scene in history occurred on December 29, 1940, during the German occupation of France in World War II. Singing Marie in Donizetti’s La fille du regiment at the Metropolitan Opera, the French coloratura soprano Lily Pons unexpectedly interpolated the French national anthem, La Marseillaise, into her lesson, bringing the audience to its feet in cheers.

Cultural writer Michael Clive is program annotator for the Utah Symphony, the Louisiana Philharmonic Orchestra and the Pacific Symphony, and is editor-in-chief of The Santa Fe Opera.