Composer Zhou Tian on Transcend

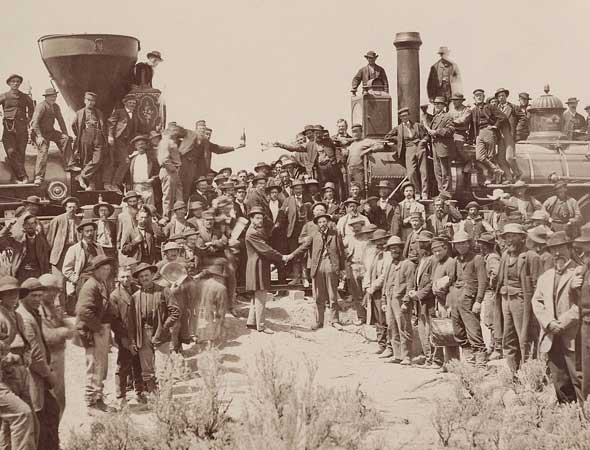

To commemorate the 150th anniversary of the Golden Spike, we, along with 12 other orchestras, commissioned Zhou Tian to create a work that told the story of this monumental moment in American history.

Read about Tian’s influences, challenges, and inspiration for this work.

What was your process like in creating this piece?

The Transcontinental Railroad transcended the different cultures and peoples to become a symbol of human perseverance and relentless pursuit of a better life for all. As a composer, I was moved to create this new work to tell a musical story, to celebrate human perseverance, and to pay tribute to my cultural heritage.

During my yearlong research and travel on this piece – and I have never done so much research for a single piece—I encountered many kind people who gave me inspirations. While in Omaha, a docent at a local library, who was railroad worker for the Union Pacific for 30 years, told me the true story of the telegraph of a single word:

“On May 10, 1869, when the Railroad was completed and the two trains met in Promontory Point, UT, a single word was sent across the United States via one of the first nationwide telegraphs to celebrate this monumental achievement. That single word was “done.” And it was sent through the Morse code.”

This was so inspiring that, as soon as he said that, I knew this story would be incorporated into the piece in a significant way. I soon decided to base the entire last movement of the piece on the rhythm of the word “done” in Morse code. Throughout the finale, “done” transforms into an exciting rhythmic motif and is passed back and forth to numerous instruments in the orchestra. Thus the title of the last movement is, you guessed it, “D-O-N-E.”

What are some of the challenges faced composing this piece?

The biggest challenge is to strike a right balance between purity of music and cultural relevance, so even for an audience who doesn’t know anything about the Transcontinental Railroad they can still enjoy “Transcend” just as an exciting and moving piece of music.

How has this work taken on personal meaning for you?

Begun in 1862 and completed in 1869, the Transcontinental Railroad effectively linked the US from east to west for the first time. Its cultural heritage includes the contribution of a thousands-strong Chinese and Irish workforce who toiled in severe weather and cruel working conditions. Numerous “hell on wheels” towns proliferated along the construction route and became famous for rapid growth and infamous for lawlessness. As the settlements pushed westward, there was a mixing of ethnic groups and cultures. Unfortunately, as the daunting task of laying tracks over difficult terrain increased, many workers perished, and many of the rest were denied the American dream by the enactment of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. But those who stayed brought traditional art and music into the fabric of American culture.

As a Chinese-born composer who immigrated to this country, educated at the nation’s top music schools, and now serving at one of its finest institutions, I was moved to create this new work to tell a musical story, to celebrate human perseverance, and to pay tribute to my own cultural heritage. When I learned that 13 American orchestras—many of which located along the route of the Railroad—would join forces together to commission and premiere this new work across the country, I was truly honored, as I knew the significant cultural impact this project would entail.

As a composer, what are some of your influences?

I’m a firm believer that innovation and thorough understanding and respect for the tradition go hand-in-hand in creating a satisfying symphonic work. As a composer, I am empowered by the tradition, from medieval chants and Chinese folk music to Brahms and Stravinsky.

I grew up in a family that appreciates all kinds of music. Dad was a composer of commercialized music (think SNL Chinese version; he was the music producer for those types of shows) so I grew up practicing Beethoven on the piano as well as playing/arranging Jazz and pop tunes with my dad. My teachers, when I arrived in America to study at the Curtis Institute and Juilliard, were all “American symphonists” with music heritage from Barber and William Schuman, all of which have had great influences on my music.

Outside of music, my recent works were inspired by things as different as a disappearing past due to industrialization (“Trace”); Father-daughter relations of a Spanish hero (“Viaje”); connecting Bach with Erhu, a traditional Chinese instrument (Violin Concerto); and mixing Jazz and wind ensemble (“Petals of Fire”).

The last time you were with us in Salt Lake, you taught a master class. What did you take away from that experience?

It was a wonderful experience. As a matter of fact, soon after that masterclass, I received an email from a local teacher at Highland Park, who asked his 4th-grade classes if they were going to write a piece about the Transcontinental Railroad what they would include.

I was so happy to see that some of the ideas completely lined up with how I thought about the piece! Here are two examples that the 4th graders wrote that made into the first movement, “Pulse”:

- “Flat’ melodies to symbolize the plains and deserts, “jagged” melodies to symbolize the Sierra Nevada and Rocky Mountain ranges” (I started the piece with calm and serene strings, before bursting into a constant pulse of 152 BPM).

- “Huge surprising blasts inspired by dynamite and blasting through mountains and rocks.” (I created violent, percussive poundings that occur from time to time, which are like blasts of dynamite, evoking the tension and suspense of man versus nature.)

So thank you Highland Park 4th Graders!!