Rachmaninoff – Concerto No. 2 in C Minor for Piano and Orchestra

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873 — 1943): Concerto No. 2 in C minor for Piano and Orchestra, Opus 18

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons; 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba; timpani, bass drum, crash cymbals; strings

Performance time: 32 minutes

Background

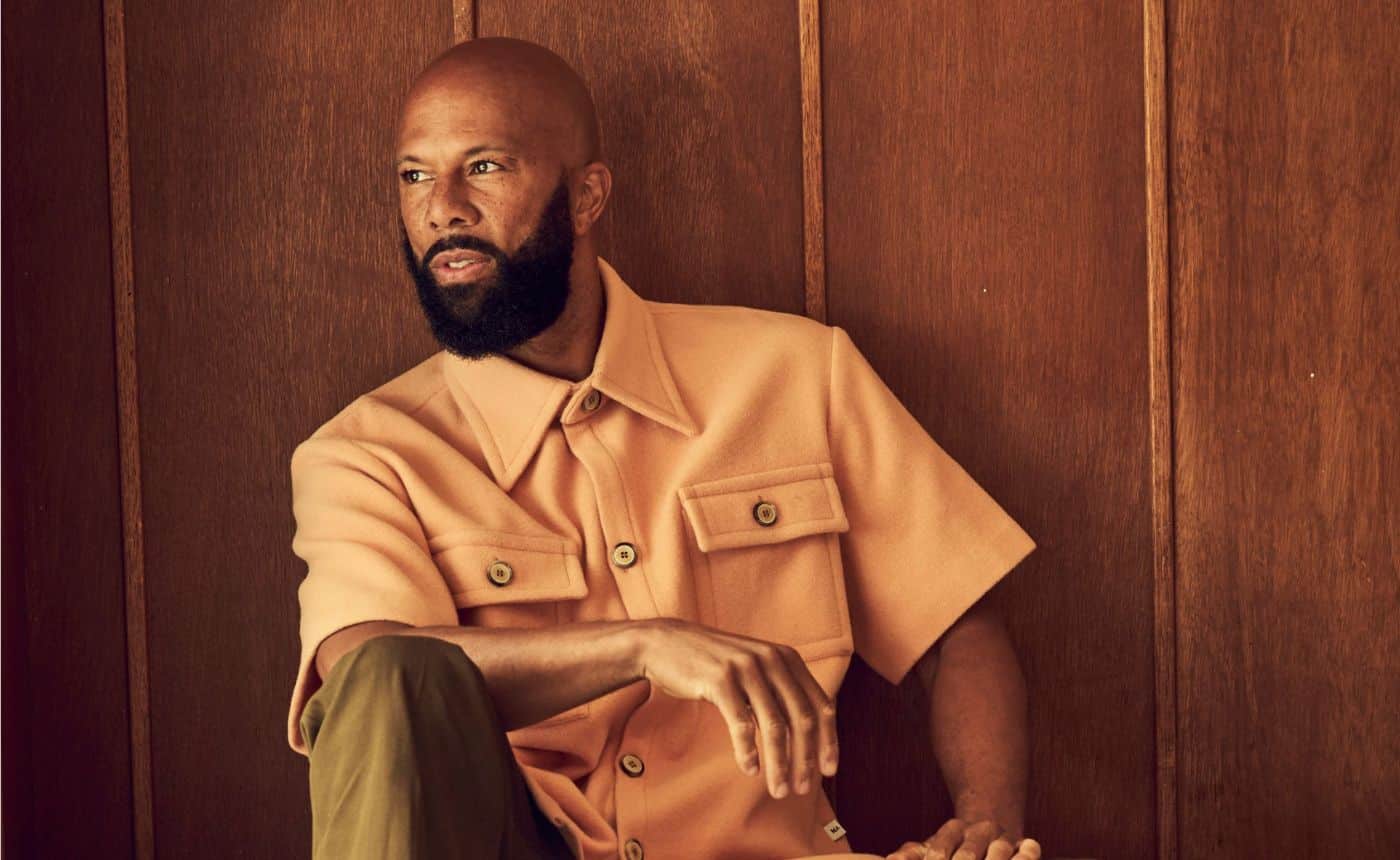

Though he was born before the last quarter of the 19th century began, Rachmaninoff was essentially a figure of the 20th century. Still, we can call him the last of the Russian Romantics; his sound was rooted in the 1800s and in the Russian nationalist composers dating back to Glinka and Tchaikovsky. He was also one of the greatest pianists of his day, and perhaps one of the greatest ever. With superlative technique and hands of enormous reach (possibly the result of Marfan syndrome, a congenital cardiac condition), he was ideally suited to perform works of power and Romantic sweep. Trained as a pianist as well as a composer in Moscow and Saint Petersburg, Rachmaninoff focused on the piano in both composition and performance. Of his three concertos, the second is both the most popular and the most admired among critics. This is the composition that made his reputation. By now, fans and musicians have affectionately named his concertos “Rocky 1,” “Rocky 2” and “Rocky 3,” but it was Rocky 2 that first acquired its nickname. And, appropriately enough, it takes a heavyweight talent to go the distance with it.

The concerto’s success was hard-won. Composed between the autumn of 1900 and the spring of 1901, it followed by three years the dismal reception of Rachmaninoff’s first symphony, which proved a setback to his musical ambitions (despite the acclaim it earned later). Long troubled by clinical depression, the well-born Rachmaninoff benefited from excellent medical care and the support of friends and colleagues, who encouraged him to rededicate himself to piano composition. It was good advice, and helped him to work free from a creative stasis. In fact, while many concertos are dedicated to the soloists who premiered them, this one is dedicated to Rachmaninoff’s physician, Nikolai Dahl.

It was the success of this concerto combined with the relative failure of Rachmaninoff’s first symphony steered toward a career that made him a celebrity in America, a virtuoso pianist performing his own virtuosic compositions. He would not attempt another symphony until 10 years after his first, and the merits of his great orchestral compositions would not be fully appreciated until years after his death. Today, even Rachmaninoff’s flair as an opera composer is being rediscovered.

What to Listen For

With his impressive technique, Rachmaninoff was ideally suited to perform his own piano works, and did so on concert tours in the U.S. and elsewhere. Listening to his concertos, we sense the perfect match between his physical gifts as a soloist and his style as a composer: These are compositions of dynamic extremes and singing melodies that require both power and speed. The aural effects are spectacular, requiring a huge note span, blinding dexterity, the ability to delineate multiple voices, and the control to delineate subtle gradations in tempos and dynamics. Through all of that, Rachmaninoff requires the pianist to spin a silken cocoon of sound that is voluptuous and quintessentially Romantic.

No one combines musical intimacy and sensuality with grand, even monumental sound the way Rachmaninoff does, especially in this concerto. One can hear the brooding depressive as well as the ardent romantic in every bar. In the first movement, marked moderato and written in C minor, an opening of intense foreboding builds through a series of powerful, chiming chords by the soloist. As the tension builds to a breaking point, the piano breaks into a sweeping main theme that is taken up in the violins, but that quickly engulfs the entire orchestra. From this moment on — indeed, from the initial sounds of the piano’s lone voice in the concerto’s introduction — this is a hugely scaled musical statement that balances sweeping, melancholy phrases with melodies that express the sweetness and pain of romantic yearning. Throughout we hear both the chilly bready of Russia outdoors and a moody interior landscape. When a rolling theme emerges, its march tempo gives it the quality of an inexorable machine, with only the solo piano to challenge it.

Slow chords in the strings open the second movement, an adagio that moves from C minor into E major. While the piano delineates a theme through fleet, poetic arpeggios, the overall mood remains melancholy, with a short exchange between orchestra and piano developing the movement’s motifs. Yet this tinge of sadness does not overwhelm, perhaps balanced by the sense of romance and melodic richness. The concerto’s songful quality, which gave rise to two Frank Sinatra tunes based on the first movement alone (“I Think of You” and “Ever and Forever”), takes full flight in the lush, gorgeous third movement, marked allegro scherzando. This movement is built around a melody that could be the distilled essence of romance, and that forms the basis of the song “Full Moon and Empty Arms.” It has been excerpted in dozens of movies to convey the exquisite pleasure of love anticipated…and the exquisite pain of love unfulfilled. It can also be said to have saved Rachmaninoff’s life: When he composed it and discussed it with colleagues, it secured his more optimistic outlook on his composing prospects. This is the theme that turned Brief Encounter into a three-handkerchief weepy; “delicious” is one of the words Marilyn Monroe uses to describe it in The Seven Year Itch. “Every time I hear it, I go to pieces!” she exclaims.

The concerto ends in a flourish of virtuosity and optimism that may well reflect the composer’s rising optimism during its composition, when he was buoyed by colleagues’ encouragement. The last movement, an allegro, opens with an introduction that moves away from the previous movement’s E major, where the music was lush but the emotions lingered in an atmosphere of twilit moodiness. To close, it transitions from C minor to C major with ever-increasing tension and energy. The final thematic statements and coda are resolved in C major, in a loud and ecstatic finale.