Mahler Listening GuideSymphony no. 1 in D Major

by Bettie Jo Basinger

Gustav Mahler

Work History

Gustav Mahler finished his first symphony in March of 1888 while employed as the second conductor at the Stadttheater (City Theater) in Leipzig. Although he may have started work on the piece as early as 1884, evidence suggests that the bulk of composition took place within the six weeks immediately prior to the symphony’s completion. A mere two months later, the composer departed from the Stadttheater to become the Artistic Director of the Royal Hungarian Opera, and the piece therefore received its first performance in Budapest on 20 November 1889 with Mahler himself conducting.

At this premiere, the composer designated the work not as a symphony, but as a “symphonic poem in two sections.” The opening section consisted of three movements: the present-day first movement, an Andante that Mahler eventually withdrew from the piece, and the music we now know as the second movement. Following this, the final section of the so-called “symphonic poem” presented what would become the third and fourth movements of the four-movement Symphony No. 1.

Perhaps because the Budapest performance proved unsuccessful, Mahler revised the symphony between 1893 and 1896. Since no copy of the original version survives, the full extent of the changes remains unknown; however, a letter Mahler wrote to Richard Strauss on 15 May 1894 intimates drastic modification to the instrumentation. Further alterations include the addition of a program, and the composer circulated his new “explanation” for the piece on 27 October 1893 in Hamburg, where Mahler was then serving as the chief conductor at the Stadttheater. Now collectively dubbed “Titan, a tone poem in symphonic form,” each of the five movements received a title, and three of them also took on brief verbal descriptions. Mahler retained these titles and summaries, with only minor modifications, for a Weimar performance conducted by Strauss on 3 June 1894.

The Titan of the title relates to an 1800-1803 novel of the same name by Jean Paul, which narrates a convoluted tale (in four volumes) of a man who must discover his hidden past, find his ideal bride, and assume the throne of a small German principality. Other aspects of the 1890s program also allude to works by Jean Paul. For example, Mahler retained the subdivision of the five movements into two sections, and the label he attached to the first section—”From the Days of Youth; Flower, Fruit and Thorn Pieces”–recalls Jean Paul’s novel Siebenkäs (1796-1797), the full title of which reads Flower, Fruit and Thorn Pieces; or the Married Life, Death, and Wedding of Siebenkäs, Poor Man’s Lawyer. Moreover, the composer gave the Andante movement –i.e., the one he would later discard—the appellation “Blumine,” and this evokes the same author’s Herbst-Blumine (Autumn Flowers) of 1810-1820.

Commonly translated as Grotesque Dwarves, Various Hunchbacked Figures offers a more literal translations of Jacques Callot’s Varie figure gobbi, a collection twenty etchings of dwarves. Callot titled this image “L’homme au gros ventre orné d’une rangee de boutons” (“Man with a Great Belly, Ornamented with a Range of Buttons”).

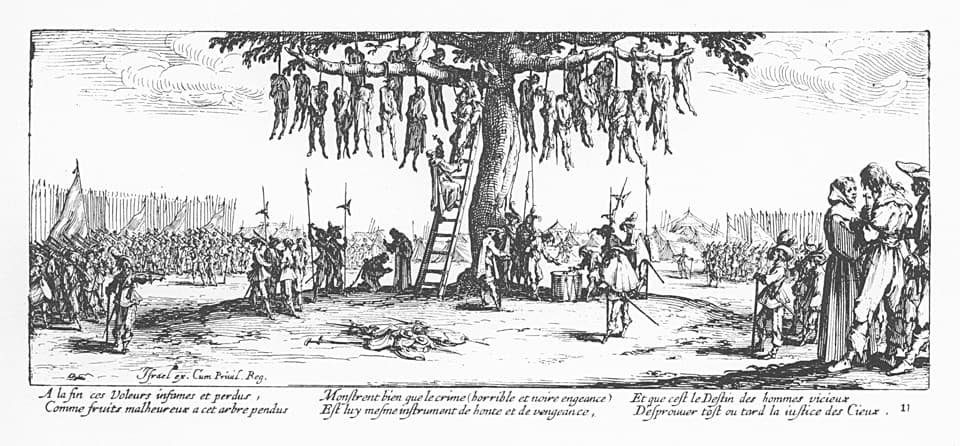

Yet Mahler complicates the Jean Paul scenario with additional references, both programmatic and musical. The third movement’s verbal summary—”Stranded! (Death March in the manner of Callot)”—mentions Jacques Callot, a Baroque engraver known for both his fanciful images and frank depictions of war, as well as a South-German fairy tale in which forest animals display mock grief while staging a funeral procession for a deceased hunter. Furthermore, the music quotes the children’s song Bruder Martin (known as Frère Jacques in France and Are You Sleeping? or Where is Thumbkin? in the United States), as well as a lied from Mahler’s own Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of Wayfarer, 1883-1885; revised and orchestrated, 1891-1896). The first movement likewise quotes another song from this same cycle, and had the “Blumine” movement stayed in the symphony, it would have drawn from the incidental music Mahler wrote in 1884 for Joseph Victor von Scheffel’s play Der Trompeter von Säkkingen (The Trumpeter from Säkkingen) of 1853.

Callot’s 1633 series of etchings entitled from the series Les misères et les malheurs de la guerre (The Miseries and Misfortunes of War) captures the atrocities of war, especially violence against civilians. Although the images depict no particular battle, occupation of Lorraine—where Callot resided—during the Thirty Years’ War likely influenced the series. The publisher issued “La pendaison” (“The Hanging”) as the eleventh of eighteen etchings in the set.

It seems unlikely that the composer spun this web of allusions—which also incorporates materials from Liszt’s Dante Symphony (1855-56) and Wagner’s Parsifal (1887-1882) in the finale—either by coincidence or due to a lack of invention. Instead, Mahler’s references hint at a very personal and abstruse “meaning” in the First Symphony. The composer’s decision to embed Gesellen songs in two of the symphony’s movements serves as a case in point. Mahler originally penned this collection for soprano Johanna Richter, even though their romance was failing at the time of composition, and it comes as no surprise that Mahler felt attracted to another unattainable woman—Marion von Weber, wife of composer Carl Maria von Weber’s grandson—in late 1887 and early 1888. But while he denied none of this backstory, Mahler insisted that his unhappy love affairs functioned only as the impulse behind the music, rather than its content.

A letter that Mahler wrote to music critic and composer Max Marschalk on 20 March 1896 potentially clarifies the nature of the symphony’s “content.” In regards to the third movement, Mahler states, “It is true that I received the external inspiration for the third movement from the well-known children’s painting [The Hunter’s Funeral]. Only the mood matters, and out of it—abruptly, like lightning out of a dark cloud—leaps the fourth movement. It is simply the outcry of a deeply wounded heart preceded by that very eerie, ironic, and brooding sultriness of the death march.” Thus, Mahler implies that the core of Symphony No. 1 concerns the elucidation of emotion, not the depiction of paintings or fairytales, let alone the quotations of pre-existing music.

Ultimately, Mahler suppressed the program of his first symphony. He published the work in its four-movement form and without its programmatic synopsis in 1899, and this general shape persisted through subsequent revisions the composer implemented in 1906. Listeners familiar with the piece’s history (in the early-twentieth century, through the twenty-first), as well any individuals able to recognize Mahler’s musical allusions, must decide for themselves how these external references should guide reception of this composer’s music. Presumably the composer would prefer his audiences consider only the emotions connected to them. For this reason, the listening guides below generally do not outline the music of the First Symphony in terms of the programs that circulated at performances in Hamburg (1893) and Weimar (1894). They do, however, draw upon Mahler’s correspondence when his commentary describes this piece in terms of emotion—even when that emotional depiction has grounding in the “Titan” program.

The listening guides do not include the “Blumine” Andante, since Mahler withdrew the movement before finalizing the symphony. Nevertheless, Mahler specialists believe they identified it in 1968. Youtube has several accessible recordings available.

Approximate Time in performance: 55-60 minutes

Instrumentation:4 flutes, with 2 alternating on piccolos; 4 oboes, with 1 alternating on English horn; 4 clarinets, with players alternating on E-flat clarinet and bass clarinet; 3 bassoons, with 1 player alternating on contrabassoon; 7 French horns; 5 trumpets, with the 5th playing only in the last movement; 3 trombones; Tuba; 4 timpani, played by two percussionists; Cymbals, both crash and suspended types; Triangle; Tam-tam; Bass drum; Harp; Violins; Violas; Cellos; Basses

Listening Guide for the First Movement

The opening movement of Mahler’s First Symphony begins with an introduction marked “Slow. Dragging. Like a sound of nature” (“Langsam. Schleppend. Wie ein Naturlaut”). Here Mahler presents the materials that will generate the rest of movement—as well as many of the melodies that will appear in the remainder of the symphony—over hushed, sustained A’s. These germinal ideas consist of a series of descending fourths; an ascending fanfare stated first by the clarinets in their low register and later repeated by offstage trumpets; and the call of a cuckoo that audibly relates to the descending fourths. These materials initially cede to a lyrical melody in the French horns, and then to a chromatic bass line as the main body of the movement approaches.

When the tempo speeds up, the sonata form traditionally used in symphonic first movements commences. However, Mahler modifies this formal scheme by omitting the contrasting theme. Instead, he presents only one melody, a tune seemingly derived from both the cuckoo call and the descending fourths of the introduction. Nevertheless, this melody existed prior to its use in this symphony. Mahler initially composed it as a song setting for his own poem “Ging heut’ morgen übers Feld” (“I went over the field this morning”) which he included as the second song of Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen.

Ging heut’ morgen übers Feld

Tau noch auf den Gräsern hing

Sprach zu mir der lust’ge Fink

“Ei du! Gelt? Guten Morgen! Ei gelt?

Du! Wird’s nicht eine schöne Welt?

Zink! Zink! Schön und flink!

Wie mir doch die Welt gefällt!”

Auch die Glockenblum’ am Feld

Hat mir lustig, guter Ding’,

Mit den Glöckchen, klinge, kling

Ihren Morgengruß geschellt:

“Wird’s nicht eine schöne Welt?

Kling, kling! Schönes

Wie mir doch die Welt gefällt! Heia!”

Und da fing im Sonnenschein

Gleich die Welt zu funkeln

Alles, Ton und Farbe gewann

Im Sonnenschein!

Blum’ und Vogel, groß und klein!

“Guten Tag! Ist’s nicht eine schöne Welt?

Ei du! Gelt? Schöne Welt?”

Nun fängt auch mein Glück wohl an?

Nein! nein! Das ich mein’

Mir nimmer blühen kann!

I went over the field this morning

Dew still hung on the grasses

The merry finch spoke to me

“Hey you? Right? Good morning! Hey, isn’t it?

You! Isn’t it a beautiful world?

Chirp! Chirp! Nice and sharp!

How the world pleases me!”

Even the bluebells in the field

In cheerful spirits, merrily rung

With little bells, ding, dong

Their morning greeting:

Isn’t a beautiful world?

Ding! Ding, dong! Beautiful thing!

How the world pleases me! Hooray”

And there in the sunshine

The world immediately began to sparkle

Everything gained sound and color

In the sunshine!

Flower and bird, big and small!

“Good day! Isn’t it a beautiful world?

Hey, you! Isn’t it? A beautiful world?”

Now will my happiness also begin?

No! No! The happiness I mean

Can never bloom for me!

The text of “Ging heut’ morgen” song concerns nature, and this seems appropriate for the “Like a sound of nature” indication written on the first page of music. Yet while the poem does include the sounds of birds chirping and bluebells “ringing,” the poetry primarily concerns the contrast between the blithe natural world and a persona at odds with it.

After a repeat of the exposition, the development section starts in much the same manner as the introduction. (Some commentators, in fact, regard this portion of the score as a “new beginning” rather than the development. This seems justified given that Mahler will soon return to the initial key.) Yet this time, the germinal motives yield to a horn fanfare that, in turn, moves to a lyrical melody in the cellos. Although the latter sounds fresh, it combines ideas from the exposition’s song and the descending fourths of the introduction.

As the development progresses, Mahler continues to alternate between his previously-heard materials as he moves through other keys. Ultimately, he settles on a new motive—though it nonetheless feels familiar (since, for example, its ascending stepwise motion recalls both the chromatic bass line and “Ging heut’ morgen”). This builds until the introduction’s fanfare breaks through to loudly proclaim the start of the recapitulation.

During the brief recapitulation, melodies from both the exposition and development recur in the home key. To this Mahler appends a coda that lasts at most 15-20 seconds. Natalie Bauer-Lechner, an accomplished violinist and talented amateur writer, recorded that the composer once described this passage as follows: “My hero breaks out in laughter and runs away.” Presumably this hero refers to the “Titan” temporarily indicated by Mahler’s short-lived title for the symphony; more importantly, the short, detached notes of this coda certainly seem compatible with the imagery of this quotation.

Listening Guide for the Second Movement

Although Mahler labeled the second movement as a scherzo in early incarnations of his First Symphony—and for this reason, many commentators continue to refer to the movement as such—his final revision carries only the heading “Kräftig bewegt” (“Strongly moving”). Nevertheless, even without the word “scherzo” appearing on the score, the composer retains the A B A structure (i.e., dance 1, dance 2, dance 1) that has shaped dance movements of symphonies since the eighteenth century. In this case, however, Mahler chose to use the ländler as his dance type.

The A section begins with the celli and basses sounding a figure that derives from the descending fourths heard in the first movement, above which the violins “whoop” a few times before beginning the main ländler tune. This melody again resembles the opening movement, especially through its stepwise ascent and closing gesture that recalls the previously-heard cuckoo calls; small turn figures even suggest fragments of “Ging heut’ morgen.” After repetition, variation, and an additional heightened restatement of these ideas, this first portion of the second movement comes ringing to its conclusion.

The contrasting dances presented in the B sections of both symphonic minuets and scherzos generally receive the designation “trio” (due to the tradition of employing reduced orchestration—¬originally two oboes and bassoon), and this portion of Mahler’s movement constitutes no exception to the rule. Here a solo horn announces a slower tempo, as well as a gentler, more lyrical character. The composer thus moves into more waltz-like music that at times evokes the dance movement of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony in E minor (1888)—yet likely by coincidence, since Tchaikovsky did not finish work on this piece until a few months after Mahler completed the initial version of his First Symphony— before the ländler returns to round off the movement.

Listening Guide for the Third Movement

Marked only as “Feierlich und gemessen, ohne zu schleppen” (“Solemn and measured, without dragging”), the third movement of the symphony nevertheless clearly presents the listener with a funeral march. Yet as the audience starts to perceive that the composer is quoting the children’s song Bruder Martin, it also becomes evident that this music does not represent a typical example of this kind of piece. In order to make his melody more suitable for the suggestion of a funeral procession, the composer has recast it in the minor mode and placed its first statements in a round for unconventional instruments: solo bass, solo bassoon, and solo tuba. More and more instruments join the round as the timpani obsessively sound a brooding march rhythm—which relates to the first movement’s descending fourths. Other players, like the oboe and shrill E-flat clarinet, add a countermelody to the mix. The music builds to a peak above the rumblings of a tam-tam, and then the march subsides to usher in the next portion of the movement.

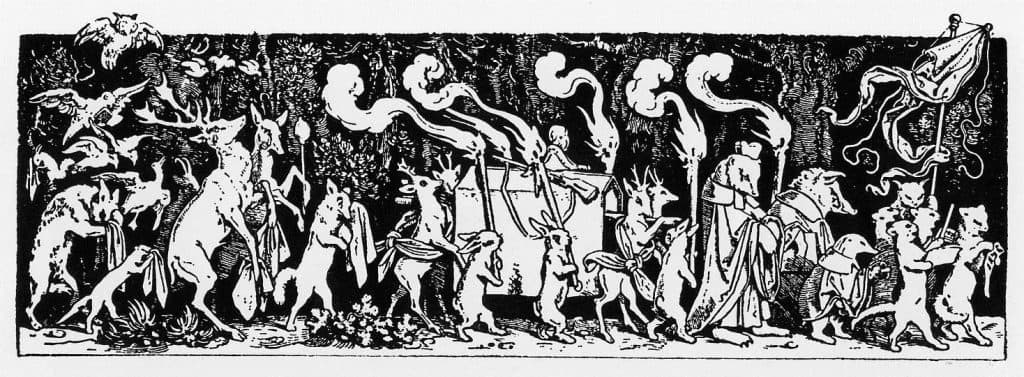

As mentioned above, Mahler’s discarded program linked this movement both to Callot and a fairytale in which forest animals lead a funeral procession in honor of a fallen hunter. While scholars now believe that Moritz von Schwind’s drawing of this folk scene instead served as the composer’s inspiration, the scenario of the huntsman’s funeral provides a reasonable explanation for Mahler’s curious (if macabre) decision to base a funeral march on a children’s melody. However, little beyond the irony of the animals’ false sorrow suggests the dances—which evoke the Jewish genre of klezmer—that follow the funeral march in the score. The music now alternates between two hyperbolized dances, the second of which Mahler asks the performers to play “mit Parodie” (“with parody”). Again regaling the listener with unique orchestration—a pairing of oboe and trumpet duets proclaims the first dance, while clarinets accompanied by the klezmer standard of bass drum and cymbal deliver the second—each appears two times before echoes of the funeral march whisk away this section’s exuberance.

Moritz von Schwind’s drawing Wie die Tiere den Jäger begraben (As the Animals Buried the Hunter) of 1850, here rendered as a woodcut, possibly inspired the third movement of Mahler’s Symphony No. 1.

Next the composer moves into a lyrical passage that quotes another lied from the Gesellen songs. This time, Mahler draws upon the final lied in the cycle, a setting of another of his own poems entitled “Die zwei blauen Augen von meinen Schatz” (“The Two Blue Eyes of My Sweetheart”). Because this text describes someone mourning a lost love—and portions of its musical setting employ the same march rhythms presented in the timpani at the head of this orchestral movement—the song seems an appropriate choice for a symphonic funeral procession, even though its programmatic connections to Bruder Martin, the mock grieving of forest animals, and Jewish dance music remain nebulous. In contrast, the prevalence of fourths in “Die zwei blauen Augen” connects to a great deal of the first movement’s music, and Mahler may even recollect some of the figuration of “Ging heut’ morgen, ” though heard here at a much slower pace.

Die zwei blauen Augen von meinem Schatz,

Die haben mich in die weite Welt geschickt.

Da mußt ich Abschied nehmen vom allerliebsten Platz!

O Augen blau, warum habt ihr mich angeblickt?

Nun hab’ ich ewig Leid und Grämen!

Ich bin ausgegangen in stiller Nacht,

Wohl über die dunkle Heide.

Hat mir niemand Ade gesagt.

Ade! Mein Gesell’ war Lieb’ und Leide!

Auf der Straße steht ein Lindenbaum,

Da hab’ ich zum ersten Mal im Schlaf geruht!

Unter dem Lindenbaum,

Der hat seine Blüten über mich geschneit,

Da wußt’ ich nicht, wie das Leben tut,

War alles, alles wieder gut! Everything,

Alles! Alles! Lieb und Leid! Everything!

Und Welt und Traum!

The two blue eyes of my sweetheart

They have sent me into the wide world.

I must say goodbye to this well-loved place!

O blue eyes, why did you look at me?

Now I have eternal sorrow and grief!

I went out into the quiet night,

Well across the dark heath.

No one said goodbye to me.

Goodbye! My companions are love and sorrow.

A linden tree stands on the road,

There I found rest in sleep for the first time!

Under the linden tree,

That snowed its blossoms over me,

I knew not, how life went on,

everything was good again!

Everything! Love and sorrow!

And world and dream!

Since “Die zwei Blauen Augen” itself resembles a funeral march, Mahler can move into the symphony’s final presentation of its funeral music without any kind of transition. This time, however, the Jewish dances invade the scene, thus throwing the music temporarily off-kilter. Mahler nonetheless soon sorts things out, and the music fades away as if the procession has moved off into the distance.

Listening Guide for the Fourth Movement

In a conversation with Bauer-Lechner occurring in November of 1900, Mahler described the opening of his fourth movement as a “horrible outcry” in which “[our] hero is completely abandoned, engaged in a most dreadful battle with all the sorrow of this world.” This provides an apt metaphor for the cymbal crash and dissonance that initiate the ¨Sürmisch bewegt” (“Stormily moving”) introduction to the finale. Tumultuous arpeggios and scales then ensue in the strings, punctuated by sneering triplets as well as rising lines in the brass that anticipate some of the movement’s primary materials. After these brass fragments build to a fortissimo peak, the exposition of the sonata-form movement begins.

The first of the exposition’s themes combines the two rising lines stated in the brass during the introduction. The resulting melody’s opening gesture—a short note followed by three longer ones—derives from a Gregorian chant named “Crux fidelis” (“Faithful Cross”) that Liszt frequently used in his music to symbolize the crucifix, though Mahler slightly modifies its intervals so that it conforms to his minor key. Moreover, the “Crux fidelis” excerpt, when taken together with the next eight notes of the finale’s first theme, restates the ostensibly “new” motive introduced in the build up of tension immediately prior the climax (and recapitulation) of the symphony’s first movement.

After substantial elaboration and variation of this theme’s melodic components, the music fades (though not before the brass can get in a few more “sneers”). From this quiet, the exposition’s lyrical second theme materializes in a contrasting key and with a “Sehr gesangvoll” (“Very songlike”) indication. Many Mahler specialists maintain that its materials recall the discarded “Blumine” Andante; regardless, the melody’s idyllic calm and inherent beauty provide a stark contrast with the music of the finale heard thus far. Yet the diverging mood proves short lived, as “Crux fidelis” and the sneering triplets mingle with the first movement’s chromatic bass line and descending fourths to reestablish a sense of unease.

Another “Stürmisch bewegt” passage heralds the start of the development. This portion of the movement commences with “Crux fidelis” and a descending chromatic line taken from Liszt’s Dante Symphony (a work in which “Crux fidelis” figures prominently), but new derivations of the exposition’s first theme soon take over. Ultimately, however, fanfares reminiscent of the first movement emerge from the din, and a pairing of “Crux fidelis”—now set in the major mode and with its original intervals restored—and a brief quotation from Wagner’s Parsifal immediately succeeds it. Next, the trumpets attempt to lead off a chorale as they descend stepwise through a series of fourths, although restoration of the minor key and turbulent atmosphere rudely disrupt their efforts.

But this storm-and-stress interruption does not last long. The “Crux fidelis”-Parsifal combination victoriously returns, promptly followed by the chorale previously endeavored by the trumpets. Its continuation in the French horns—which drops the stepwise motion—makes obvious the connection between this idea and the opening movement’s series of descending fourths, and it also seemingly presents a grandiose culmination for the fourth movement. Nevertheless, Mahler still has not recapitulated the materials of his exposition, and the finale consequently cannot yet end.

After another hearing of motives from both the first and fourth movements’ introductions, the composer marshals in his recapitulations with the return of the song-like second theme, though he atypically places it outside the home key. The exposition’s initial melody soon recurs as well, though it promptly dissolves into repetitive fragments, including those driving the climactic build up of the first movement. And much like this opening movement, fanfares resound at the high point, but they cede to Mahler’s chorale materials before a brilliant coda closes the symphony.

About the Author

Bettie Jo Basinger has been teaching at the University of Utah since 2007. She has both a Master’s Degree and PhD in Musicology—as well as a Bachelor’s in French Horn Performance—from UCLA. Although her research interests include the entire symphonic repertoire, Dr. Basinger specializes in the orchestral program music of the nineteenth century, particularly the symphonic poems of Franz Liszt.