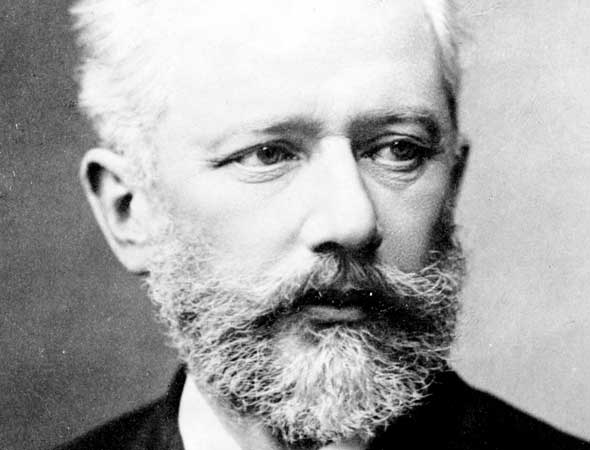

TCHAIKOVSKY – Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74, “Pathétique”

Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky

- Adagio – Allegro non troppo

- Allegro con grazia

- Allegro molto vivace

- Finale: Adagio lamentoso

BACKGROUND: Tchaikovsky was acutely aware—perhaps unrealistically so—of his image, both as a composer whose reputation would survive him, and as a public figure in Russian society. He knew that since Beethoven, the symphony was a form that serious composers reserved for big ideas and “programmatic” music that might have a narrative line or an intellectual agenda connected with the philosophical ideas of greatest concern to them. His fourth symphony, which predates the Pathétique by about 15 years, hews close to this model of symphonic writing. Impressed with the musical representations of fate that he had heard in Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 and Bizet’s Carmen, he made his fourth symphony an account of a fateful struggle for his own destiny and his yearning to live a life of mature respectability.

By 1892, when he was working on early sections of a sixth symphony in E-flat major, Tchaikovsky was one of the most famous composers in the world — a man whose fame redounded to the glory of his homeland, as he had hoped it would. However, Tchaikovsky halted work on the E-flat major draft in December 1892. It was a decision that felt not like surrender, but liberation. He intended to avoid writing what he called “pure music” — that is, symphonic or chamber music — but this determination was short-lived. Within two months he began an entirely new approach to his sixth symphony, and the ideas came pouring forth. He drafted its first section in only four days and could clearly imagine the rest. Six months later, his work on the symphony was complete.

WHAT TO LISTEN FOR: The dramatically simple escape route that led Tchaikovsky out of his creative stasis seems designed to intrigue the generations of listeners who have cherished his music, and it still does. Not only is his Symphony No. 6 a programmatic work, but listening to it convinces us that the program is specific and detailed. Yet the details are unknown. He wrote his nephew that its subtext would “remain a mystery—let them guess.” Today we are still guessing.

The sound of this symphony gives us a sense of inchoate longing. It is somber, melancholy, and yearning by turns. The ovation that greeted Tchaikovsky when he took the podium in October 1893 to lead the premiere performance was not matched once the symphony ended, when the audience was left to reflect on the secrets of this moody masterpiece. Today it is esteemed as one of Tchaikovsky’s most eloquent expressions of disappointed hopes and the ache for personal fulfillment, recurrent themes in earlier works such as his opera Eugene Onegin.

The symphony’s forte passages suggest the gravity of judgment rather than triumph, while the softer passages—which dwindle down to a Guinness-record-worthy marking of “pppppp”—communicate agonized introspection. These dynamics left Tchaikovsky’s audience with a very different listening experience than they expected, and prompted the composer’s brother Modest to propose “Pathétique” as a name for the symphony.

If the symphony offers respite, it is in its interior movements: the lilt of the second movement, labeled a waltz, but actually rendered in a tricky 5/4 rhythm; and the third movement, which includes a blaring march that gleams with brass. This movement has all the ingredients for a sense of triumph…except for triumph itself. It leaves an impression of ironic disappointment, as if it were a critique of the finale that resolves Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony stated from a vantage point of greater experience.

Tchaikovsky said that he had put his “whole soul” into the “Pathétique.” We may never know the demons that inhabited that soul, but we can hear the tortured sincerity of his feelings. Those feelings ended with his tragic death, just nine days after he conducted the symphony’s premiere.