VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: Symphony No. 5

by Jeff Counts

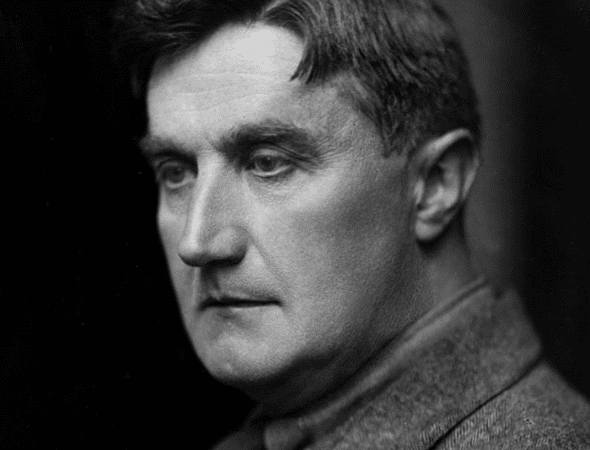

THE COMPOSER – RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS (1872-1958) – The outbreak of war in 1939 necessitated a change of focus for Britain’s composers. For many of them, this was the second moment in their lives that the needs of their countrymen temporarily silenced the call of their muses. Ralph Vaughan Williams was 67 at the time and unable to contribute at the front like before, so this meant doing good works at home. It also meant laying certain big projects aside. Campaigning on behalf of German refugees and chairing a committee for the release of interned musicians required Vaughan Williams’ full attention, so work on the opera The Pilgrim’s Progress (a stubborn work he frankly needed a break from), and the gloriously pastoral Symphony No. 5 would have to wait.

THE HISTORY – A word or two about cows. The image of a placid, cud-chewing bovine has long been associated with English provincial life. George Eliot mentioned it in her novel Middlemarch, published just one year before Vaughan Williams was born, with an observation about a rail line that was projected to cut through an area “where the cattle had hitherto grazed in a peace unbroken by astonishment”. Critics of artistic Pastoralism invoked the notion too, particularly in reference to Vaughan Williams. Peter Warlock (or was it Constant Lambert?) famously called Vaughan Williams’ Symphony No. 3 the musical equivalent of a “cow staring over a fence.” Elisabeth Lutyens decried all Pastoral composition as “cow-pat music”. And Aaron Copland apparently got in on the fun as well by comparing Symphony No. 5 to “staring at a cow for 45 minutes”. What these clever bon mots miss about Vaughan Williams is that, with his Symphony No. 3, Symphony No. 5 and other works of such calm beauty, he was not representing stasis in his music, it was stillness. The former lacks motion and ambition, but the latter includes both as potential, and the depth of that realization is meaningful. The cheeky comments above also ignore the fact that Vaughan Williams could be very un-Pastoral when we wanted to. Symphony No. 4, placed right between the two “cow-pats”, was a work of high drama and conflict. It was a necessary exercise, according to author Michael Steinberg, who claimed that “in the Fifth [symphony], cleansed by the violence of the Fourth,” Vaughan Williams had “sublimely” achieved a “clarity of sound and clarity of spirit.” He was right. That clear spirit is easily discernable in the poetic, open-hearted sounds of Symphony No. 5. Peace? Yes, and astonishment too if you care to look for it. Vaughan Williams dedicated the work, which was completed and premiered in 1943, to Sibelius.

THE WORLD – Elsewhere in 1943, the Pentagon was completed in America, the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising occurred in occupied Poland, a new volcano (Parícutin) emerged and erupted from a cornfield in Mexico and Ayn Rand published The Fountainhead.

THE CONNECTION – The last time Utah Symphony performed Vaughan Williams Symphony No. 5 was back in April 2003. Keith Lockhart was on the podium.