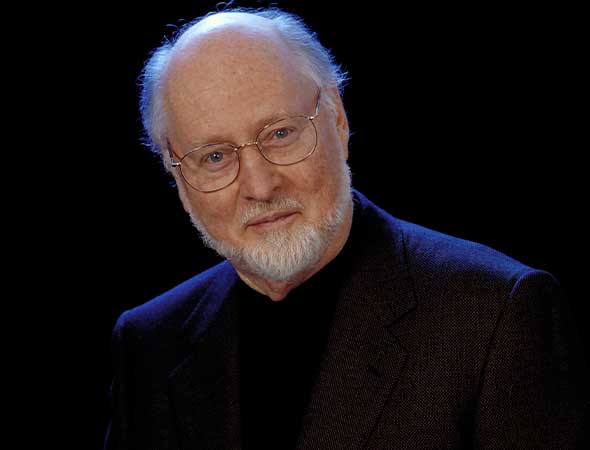

The Music of John Williams

by Matt Starling

The emergence of film as a popular art form has had a major impact on the world of classical music for over one hundred years now. During this period we’ve seen a number of composers who established their reputations in the concert hall wrote for the cinema including Saint-Saens, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Bernstein, and Glass. John Williams has developed an impressive catalog of compositions for the hall including major works for large symphony orchestras and wind ensembles, plus sixteen concertos. But it’s in the works for film that we see William’s most successful and celebrated music.

Williams grew up in New York and Los Angeles, and studied at Juilliard during the early 1950s. During this time, he gigged regularly as a jazz pianist. Soon after, Williams settled in Los Angeles and began finding work as a performer and composer for television, which facilitated his move into scoring films during the mid 1960s. Now 92 years old, Williams’ career in film has been prolific and celebrated. With 51 Oscar nominations, he is the most nominated individual in the history of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. It could be argued that no other musician from the 20th century has had a greater impact on global culture.

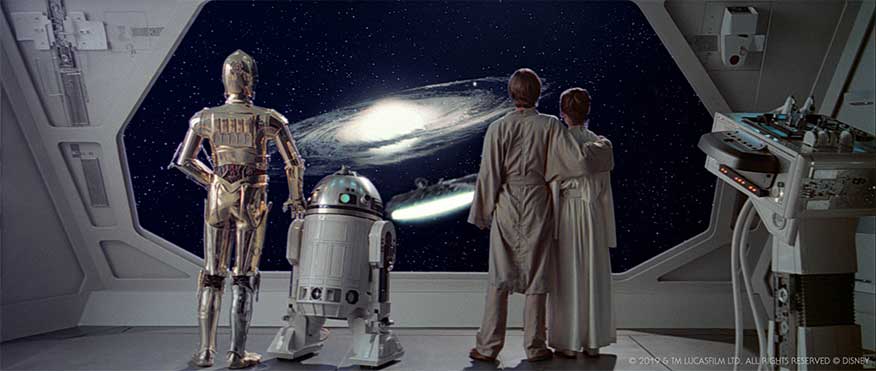

Consider how massive Williams’ audiences have been. The filmography contains a startling number of the most financially successful and critically acclaimed films from the previous fifty years. Schindler’s List, E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, Jaws, Jurassic Park, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the Indiana Jones films, Saving Private Ryan, and the first three Harry Potter movies are just a small sampling of the scores Williams has penned during his remarkable career. However the music he composed for the Star Wars franchise seems to have captured the public’s attention to a greater extent than the rest. What other music is as universally recognized and adored in today’s culture as, say, the opening theme or the Imperial March?

As the Utah Symphony performs these cherished scores, notice how equally adept Williams is at a couple of very important and very different musical tasks. On the one hand a typical film will, for a few scenes, rely on highlighting the music to do critical specific things like propel the story forward, create pure excitement that anticipates and sustains a scene, or to establish the emotional center of the scene. This is where Williams has written his most acclaimed music. However, the film composer is more often asked to stay in the background so the actors and story can remain at the center of the audience’s focus. It’s here that Williams really shines at drawing subtle and evocative colors from the orchestra. Consider the lush, gentle strings of the first moments of Yoda’s Theme and the variety of expressive instrumental techniques heard in The Magic Tree. While these compositions establish drastically different moods they do have one thing in common: neither are meant to be the focus of the viewer’s attention. Yet, this music when heard alone is without the images they were paired with is able to stand on its own in the concert hall. No small achievement.