HAYDN: Symphony No. 10

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, bassoon; 2 horns; strings; percussion; harpsichord continuo.

We consider Haydn’s of 104 symphonies to be among the high watermarks of the form, but that impressive number reflects his longevity as well as his talent; he continued to write great music into his seventies. Mozart, who died at age 35, produced 41. How many might he have composed had he lived longer? On the other hand, Mozart’s earliest symphonies sound like the compositions of a precocious child, which is what they are. Haydn’s are fully mature works. He did not attempt a symphony until his career was well under way; the opportunity simply did not present itself before that. So it is likely that the young Wolfgang began exploring symphonic form around that same time as Joseph Haydn, who was more than two decades older.

Haydn’s first important appointment as a professional musician was to the court of Count Morzin, an aristocrat of the Austrian Empire whose palace was in the village of Dolni Lukavice, near the city we now know as Pilsen (Plzeň) in the modern Czech Republic. The year was either 1757 or 1759 — Haydn would have been either 25 or 27 years of age. George August Griesinger, Haydn’s first major biographer, reported the following based on an interview with Papa Haydn himself:

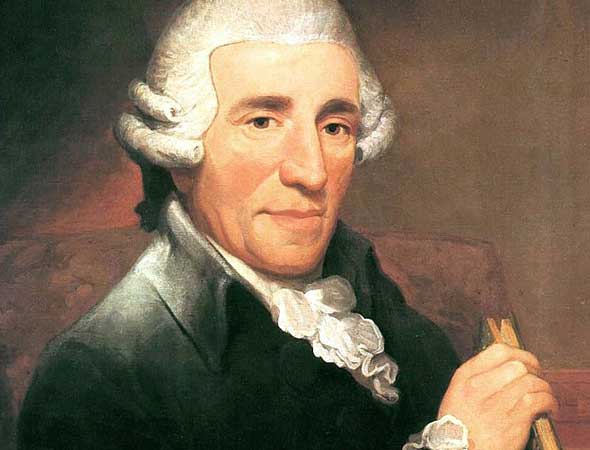

Franz Joseph Haydn

In the year 1759 Haydn was appointed in Vienna to be music director to Count Morzin with a salary of two hundred gulden, free room, and board at the staff table. Here he enjoyed at last the good fortune of a carefree existence; it suited him thoroughly. The winter was spent in Vienna and the summer in Bohemia, in the vicinity of Pilsen.

Not only the exact year, but even the particular individual who hired Haydn is contested; was it Ferdinand Maximilian Morzin or his son and heir, Karl Joseph? On such questions hang questions of objectivity in music journalism. The late H.C. Robbins Landon, an important authority on Haydn and Mozart, believed that the young Haydn’s patron was in fact the senior Count Morzin, a more powerful figure in Austrian politics. On the other hand, James Webster, writing almost 15 years later in the generally authoritative New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, identifies Haydn’s benefactor as Ferdinand Maximilian’s son, Karl.

As it happens, H.C. Robbins Landon was a generous colleague and friend to the author of the article you’re reading now — which may be one reason why I am inclined to believe him regarding the facts of Haydn’s biography. But another reason is how well it supports our understanding of Haydn’s unusual life as a composer. To put a Trekkie spin on it, Haydn lived long and prospered, applying his great musical gifts with discipline, judgment and political sure-footedness. His agreeable character and musical accomplishments had already had already become known within and outside his professional world. All of these virtues were instrumental in building his reputation as a patriarch of the classical age, and his appointment by the senior Count Morzin while still in his twenties to a position in which he could call himself Kapellmeister would have been an important early stage in his professional life. The Kapellmeister’s lifestyle during the Classical era reflects the same pattern that prevails today, with the new “season” of music beginning each fall. It has often been described as migratory, and kept Haydn where his employer wanted him — on the Count’s hereditary estate in the country during the summers, and in the thick of the Austrian capital’s musical and social scene in the winters.

The one blot on Haydn’s seemingly charmed development as a composer was his marriage to Anna Maria Keller in 1760, just a year or two after his appointment by Count Morzin. Haydn’s contract with the count expressly barred him from marriage, but he apparently was able to keep his employer unaware of his alliance with Anna — a marriage that, despite its general unhappiness, endured 40 years. At any rate, this potential obstacle proved moot, since Haydn’s patron found himself in a budget crunch within a year after the marriage, and was forced to eliminate Haydn’s position.

A setback? Nothing of the kind: Count Morzin helped Haydn gain an appointment as Vicekapellmeister in the service of the very prestigious Prince Anton Esterházy at Eisenstadt, where he worked as composer, conductor and administrator, advancing his career significantly. With the incumbent Kapellmeister in ill health, Haydn assumed that position in all but name — at a salary much higher than the amount he originally received from Count Morzin.

Haydn’s canon of 104 symphonies begins with his appointment by Count Morzin. It is believed that 11 of his early symphonies were written for the Count, though they are not numbered consecutively and there is some debate as to exactly which of these works were written for him. (The numbers range up into the thirties, with significant gaps in the chronology.) But historians place the Symphony No. 11 in the period when Haydn was composing for the house of Morzin. It was probably written around the same time as his well-known trio of symphonies Nos. 6, 7, and 8, known as “Le matin” (morning), “Le midi” (noon), and “Le soir” (evening).

In later symphonies we hear Haydn creating a sound that is familiar to us as “symphonic scale,” for an ensemble of about 60 players. (The post-Romantic symphony orchestra generally numbers at least 70, sometimes many more). But the symphonies written for Count Morzin were scaled for a smaller orchestra and had a more intimate sound; based on scores for another of Haydn’s composers, Robbins Landon estimated that Count Morzin’s orchestra comprised six to eight violins; a basso section of one cello, one bassoon and one double-bass; and a “wind-band” sextet of oboes, bassoons and horns. The resulting sound is more akin to a chamber ensemble than to that of a larger ensemble that can blast out Brucknerian thunder. What we hear is not the dramatic intensity of a Romantic symphony, but the beauty and symmetry of the Classical era at a scale that brings us close to the heart of the music, as in a chamber work. The textures are transparent, and the instruments are somewhat exposed.

The Symphony No. 11 is classed as a sonata da chiesa (a “church sonata”) not because of any sacred themes associated with it, but because of its formal structure and the alternating pacing of its four movements, which are marked adagio cantabile (slow, with a “singing” quality), allegro (fast), menuetto con trio, and presto (fast).

The symphonies Haydn composed during this period have a characteristically crisp, well-organized structure similar akin concerto grosso style, with contrasting movements and an interplay between foregrounded and backgrounded instruments. In this case, however, the final presto movement is unusual, with a brisk 2/4 time signature rather than the 3/8 tempo that was customary during the period. To come critics, this feature suggests a link to Haydn’s similarly constructed Symphony No. 5. No. 11 also boasts an unusual series of trailing eighth notes in the third movement, creating an effect of “limping syncopation.”

In much of the symphony we enjoy responsive playing between contrasting lines as the solo lines, often dispatched with high, ornate passagework, provoke larger response in the larger ensemble. But in the finale of the lively fourth movement, marked allegro, we are treated to exciting instrumental displays throughout the orchestra.