STRAVINSKY: The Rite of Spring

Instrumentation: 5 flutes (2 doubling on piccolo), 5 oboes (2 doubling on English horn), 5 clarinets, 5 bassoons; 8 horns, 5trumpets, 3 trombones, 2 tubas; strings; percussion.

For most of his life Igor Stravinsky was the most famous composer in the world, but he did not come to fame early. His reputation was made through his early ballet compositions when he was in his mid and late twenties. Le Sacre du printemps — the shock heard round the world — premiered in 1913, when he was a young composer with a growing reputation in Europe and elsewhere. It instantly transformed him into an international celebrity: brilliant, visionary and notorious.

The well-born Stravinsky had received much of his musical education through private instruction. In 1906 he was of an age when most ambitious young composers were years beyond conservatory, hoping to attract favorable attention from the music world and that was just what he wanted as well. Though he had published almost nothing of consequence, but was the private pupil and esteemed protégé of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, who recognized his promise.

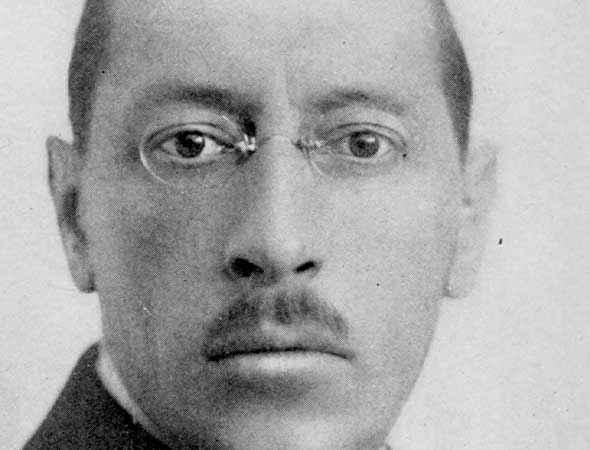

Igor Stravinsky

Stravinsky’s association with Rimsky was a credential by itself, but the young composer had no major commissions on his docket. That made him especially receptive to a suggestion from his mentor for an opera based on an enchanting tale from Hans Christian Andersen, Le Rossignol. But after a year’s work, an improbable series of coincidences brought Stravinsky the commission for The Firebird, his breakthrough ballet for Serge Diaghilev’s prestigious Ballets Russes, and he set Le Rossignol aside. Suddenly, Stravinsky was in a hothouse of international talent; the Ballets Russes’ dancers included Vaslav Nijinsky and Bronislava Nijinska, its settings and costumes were designed by such artists as Pablo Picasso and Leon Bakst, and its productions embodied all the artistic richness and ferment of Paris in the Art Deco era preceding World War I. With characteristic boldness, Diaghilev had given Stravinsky this assignment based on a single hearing of a rather slender score; its success made composer’s reputation overnight.

This success launched the beginning a transformative musical journey that continued with Petrushka and the epoch-making Sacre du printemps. In less than five years, this astounding collaboration caused sophisticated Parisians to riot at the sound of a new and revolutionary sound in music far beyond anything Rimsky imagined.

Sacre put the world on notice regarding the magnitude of Stravinsky’s genius. In one of the strangest sequences in all of cultural history, the Rite’s unfamiliar sound so enraged listeners at its Paris premiere in 1913 that the audience became a violent mob, endangering the musicians, the dancers, and Stravinsky himself. What could account for the intensity of this reaction?

The ballet, created for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes and danced by Nijinsky, did incorporate breathtakingly new musical elements: complex polytonalities that give rise to intentional dissonances, densely overlapping polyrhythms, and foregrounded percussion. But its esthetic unfamiliarity hardly seems to account for the crazed distress in the audience, where elegantly dressed strangers turned on each other with their fists. Perhaps even odder, it took just a year for the Sacre to earn cheers and bravos, making Stravinsky a hero of music. Today, that fateful premiere and the musical revolution that followed it are studied not only by music historians, but by psychologists.

Nicholas Roerich, the designer of Le Sacre du printemps (“the rite of spring”), developed the ballet’s scenario from an outline by Stravinsky in which he envisioned the stage action based on Russian pre-Christian folk rituals. Though his two earlier ballets incorporated folk elements, they did not have the elemental urgency — and frankly, the violence — of Sacre, which takes as its story line a composite pagan ritual celebrating the advent of spring. At the core of the action is a ritual sacrifice: a young virgin chosen as a human sacrifice dances herself to death, goaded on by frenzied polyrhythms propitiating the renewal of life.

After more than a century, the music of Sacre sounds thrillingly listenable now. But during rehearsals the music’s rhythmic complexity was the despair of the instrumentalists and dancers alike, who had to count aloud as they performed and would sometimes lose their place even so. For his first performance of the work with New York Philharmonic, Leonard Bernstein — a meticulous preparer who always marked his scores with detailed notations — found the score insurmountable on his own. He had to call upon the musicologist Nicolas Slonimsky, a friend of Stravinsky’s (who, like the composer, emigrated to America), for help in deciphering the rhythms.

Today the artful brutality of Le Sacre du printemps shocks no one, and its innovations have even made their way into movie soundtracks. The musicologist Richard Taruskin has suggested that the initial upset at the premiere was caused by the choreography rather than the music, and it is true that the music was performed frequently in the ensuing years while the ballet was not remounted until 1920. But after studying primary documents of the era, other researchers — including neuropsychologists who specialize in the apprehension of sound and music — disagree. Either way, the aural and visual spectacle — a booming, tuneless pulsation in the orchestra accompanying a primitive pagan rite — must have provided quite a jolt…especially following the Romantic delicacy of what came earlier in the program. It was Les sylphides, based on the music of Chopin.