BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 7

When we think of Beethoven as the Promethean composer who broke boundaries and reinvented forms, his symphonies immediately come to mind; the word “fun” does not. Yet “fun” is a word often seen in critical appreciations of his Symphony No. 7. Its exuberance makes it seem like a symphony of joyful first movements and exciting climaxes, with scarcely a relaxed moment. Despite the appeal of this symphony’s elemental melodies, its powerful rhythmic drive is the work’s emotional driver, thrilling us with a feeling of palpable freedom, like riding in a convertible with the top down on a beautiful, empty road. It’s all we can do to keep from jumping out of our seats with leaping gestures that match our feelings about the music as we listen.

This symphony’s bold, peppery repetitions, which took some of Beethoven’s contemporaries by surprise, begin in its first movement. An expansive introduction is marked Poco sostenuto, with long, ascending scales. It then gives rise to a lively Vivace that begins the symphony’s dancing rhythms (with no fewer than 61 repetitions of the note E along the way). Sudden shifts in dynamics and jagged modulations intensify the feeling of unceasing spark and pulse.

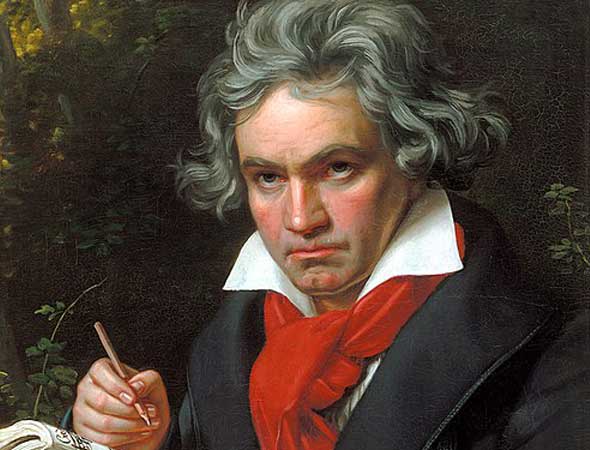

Ludwig van Beethoven

To many listeners, the second movement’s use of repetition is the most remarkably modern aspect of Beethoven’s Seventh. In most symphonies, a movement marked Allegretto might seem relatively quick; in Beethoven’s Seventh, it is the second and slowest of the four movements. But it is the movement’s use of repetition that belies its date. The impression of melody and energy is built on repetition rather than tune, looking forward to the more modern ideas of motivic and gestural development rather than a traditional, hummable theme. The development begins in the violas and cellos and moves to the violins as the violas and cellos transition to a second theme. This rotation continues with the original melody moving to the winds while the second melody moves to the first violin. This movement, with its fluid interplay of themes throughout the orchestra, has retained its popularity and has often been encored in performance.

The third movement is comprised of a scherzo in F Major paired with a trio in D Major; the trio is based on a stirring Austrian pilgrims’ hymn, and incorporates a typically thorough development section — not just “A-B-A,” but “A-B-A-B-A,” a pattern we also encounter in Beethoven’s Symphony No. 4 and in the second string quartet from his Op. 59.