MAHLER: Adagietto from Symphony No. 5

The fourth movement of Gustav Mahler’s hugely scaled fifth symphony, marked adagietto, is probably performed as a stand-alone work more often than any other single symphonic movement. Time seems to stop when we hear it. It is an exquisitely poetic meditation on the deepest sensations of feeling alive in the universe, of having a place in the boundlessness and beauty of divine creation. It is also, quite possibly, a love song without words. And within the larger musical context of the symphony itself, it is an expression of infinite serenity surrounded by fevered searching.

In his biography of Gustav Mahler, Henri-Louis de la Grange writes with painterly detail about the summer and fall of 1904, when Mahler was preparing to conduct a new production of Beethoven’s opera Fidelio while also preparing for the premiere of this symphony. The account reveals a side of Mahler we tend to forget, as well as confirming our popular image of him as an obsessive artist ardently committed to big ideas and uncompromising in his esthetic principles. Today we know Mahler primarily as a symphonist—some would say the pre-eminent symphonist since Beethoven. But during his lifetime, Mahler’s reputation rested mainly on his conducting. Appreciation of his symphonies was hard-won, barely hinting at the acclaim these masterworks would receive later. His cycles of art songs placed him within in the lineage of the foremost German-language art-song composers, but somehow did not establish him as a composer of greatness. But as a conductor of opera he was a penetrating musical analyst with a tremendous sense of theater. All of these factors helped shape Mahler’s Symphony No. 5 and helped make it a turning point in his symphonic composition.

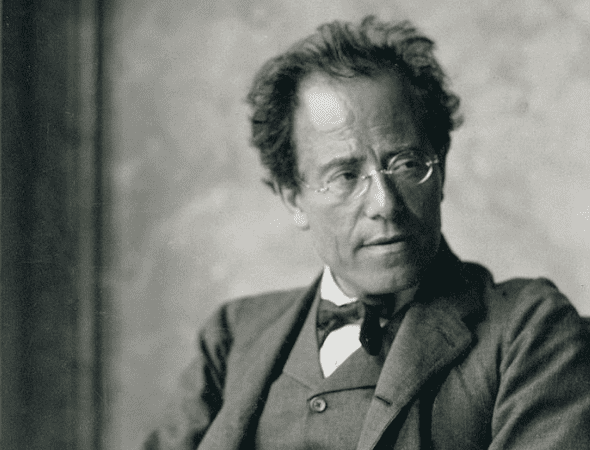

Gustav Mahler

The composer’s simultaneous focus on his Symphony No. 5 and on Beethoven’s Fidelio seems fateful. He considered it the greatest of all operas, the “opera of operas” that most fully realized the form’s potential for exploring humanity’s highest concerns. These are the concerns that pervade Mahler’s music: His symphonies and songs explore the fragility of beauty, the brevity of life, the mystery of death and the purpose of corporeal existence. In his first four symphonies, these subjects were not just embedded in the notes, but expressed verbally through the inclusion of vocal elements based on folk songs, or on Mahler’s own. Even his simplest songs contain these layers of meaning.

Mahler’s fifth symphony was his first purely instrumental work in this form. It progresses from an opening funeral march to a triumphant fifth movement—a finale that is his most emphatic affirmation of life. Is the ghost of Beethoven’s Leonore, the heroine of Fidelio, lurking in this symphony? Leonore’s faithfulness to her imprisoned husband Florestan delivers him from false imprisonment, vanquishes a tyrant, and strikes a blow for human freedom; identifying with her story, Mahler produced a work of music-theater that transformed the way we see Fidelio. And De la Grange reveals that 1904, when Mahler was working on this opera and his Symphony No. 5, was a period of joyful closeness between Mahler and his wife, whom he idolized—the formidable, captivating Alma.

We know from contemporary reports by Alma herself and by Mahler’s good friend Willem Mengelberg, the brilliant Dutch conductor, that the symphony’s achingly lovely adagietto was a very personal message to Alma, delivered wordlessly to her as a gift. While Leonard Bernstein cemented the tradition of playing it as an elegy—first in tribute to his mentor Serge Koussevitzky and later at a memorial for Robert F. Kennedy—it was likely an expression of Mahler’s undying love for his wife. For many listeners, including this one, a sense of timeless ardor pervades this movement.

When you listen to the adagietto, what will you hear? A dirge, or a love letter? A rumination on the universality of death, or an expression of the beauty of human love? Initially, cavils about Mahler’s symphonies were usually related to scope, with critics citing expansive developments that seemed disproportionate to their relatively simple themes. When advocates such as the conductor Sir Thomas Beecham championed the symphonies, their merits gained recognition. But their reputation for monumentality only increased, reinforced by a sense of the composer’s insistence upon profundity, eternal themes and, yes, death. The symphonies abound in funeral marches and chorales that suggest religious concerns (both occur in the fifth), reinforcing the idea that Mahler was death-obsessed and unremittingly profound—an obsessive composer for obsessed listeners. It’s more realistic to view his awareness of death as the philosopher’s memento mori, intended as a reminder to keep what’s important in view—a reminder that life is finite and precious, its mysteries and its brevity worth pondering.

Mahler’s Symphony No. 5 makes a breathtaking transition in the course of its five movements. It opens with a funeral march that captures us with an arresting trumpet call and a fanfare of trumpets expressed in quick, urgent triplets. The textures are brilliant, but the mood is one of frightening portent that gives way to despair as the brass-heavy march subsides into elegiac contemplation dominated by strings. Mahler’s expansive development, with each element repeated, leads the movement to a mysterious close that suggests something different is coming—as indeed it is.

Though another movement follows it, the adagietto provides the symphony with a resolution fpr all of these elements. Its long, singing lines provide a sense of serenity. Heard as an expression of love, the adagietto makes the symphony’s ultimate triumph possible, moving with a quality of ecstatic timelessness until it diminishes to a single, poetic note—an “A”—in the horn. In full performances (which last almost an hour and a half), the symphony’s final movement unfolds from this note without a pause, and leads to one of the most tumultuous expressions of triumph in music: a deliriously energetic rondo.