VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: The Lark Ascending

Instrumentation: 2 flutes, oboe, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons; 2 horns; strings; percussion; solo violin.

It may seem shocking to compare Ralph Vaughan Williams’ sylvan tone poem The Lark Ascending to the erotically sensual Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun by Claude Debussy. But before calling for your intrepid annotator’s resignation, consider how much we can learn from the similarities between these two works. Composed two decades apart — the Debussy in 1894, the Vaughan Williams in 1914 — each captures a distinctively national style at a time when English and French composers were searching for paths of escape from the harmonic experiments of Viennese and German composers. In two brief orchestral works evoking wordless creatures in nature, Debussy and Vaughan Williams capture the essence of French and English cultural traditions, showing a way forward for the composers of their respective countries.

What sounds sublimely simple and inevitable in The Lark Ascending is a melodic voice that is like England’s green and pleasant countryside distilled in music. The style is informed by the traditions of English folk songs, which Vaughan Williams studied throughout his long career, and English lyric poetry, which the Cambridge-educated composer read with an expert eye. If a Hollywood scriptwriter had to invent a musician for Vaughan Williams’s chosen task, the result would surely have been the resolute Ralph, whose terribly English family had many eminent jurists on one side and the Wedgwood pottery dynasty on the other.

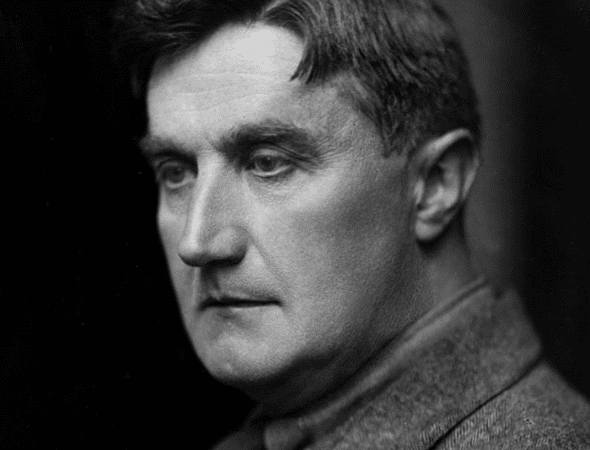

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Though the artistic Wedgwoods encouraged young Ralph’s interest in music with early instruction in theory, violin and piano, he was far from a prodigy; he struggled with his musical development, and in his Cambridge years described his own technical abilities as mediocre. But writing in the authoritative Grove, musicologist Hugh Ottaway ascribes Vaughan Williams’ difficulties mainly to his struggle to find a distinctive voice for himself and for British music. Ottaway dates the turning point to 1910, when Vaughan Williams stunned his colleagues with the Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis. The equally epochal The Lark Ascending came four years later.

The Lark Ascending is based on an important poem of that title by George Meredith dating from 1881. No less an eminence than the great World War I poet Siegfried Sassoon found “supreme” merits in the 122-line Meredith work, which invests allegorical meaning in the soaring, egoless flight of the lark over increasingly mechanized English farmland. But where Meredith’s rhyming couplets are often freighted with heavyweight poetic description, Vaughan Williams accomplishes something quite different. His music does not describe the flight of the lark; it is the flight of the lark. In the century since the premiere of Vaughan Williams’ The Lark Ascending in the Bristol town of Shirehampton, it has far surpassed its source in renown.