WAGNER: Siegfried Idyll

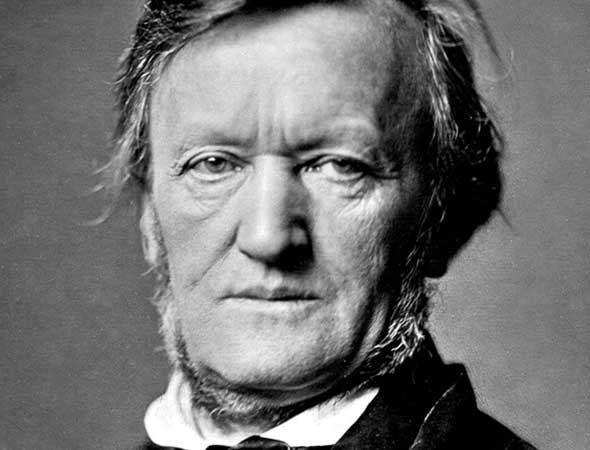

First, let’s get our Siegfrieds straight. The Siegfried of Richard Wagner’s impossibly beautiful Siegfried Idyll is not the Siegfried for whom the third opera of Wagner’s gigantic tetralogy The Ring of the Nibelung is named. Nor does it have anything to do with the gorgeous passage known as “Dawn and Siegfried’s Rhine Journey” from the prelude of the Ring’s fourth opera, Götterdämmerung, though elements from the Idyll did find their way into the Ring. In these comprehensively imagined music dramas, Wagner projects his personal cosmology onto a mythic universe — a place of normative values whose inhabitants journey toward moral perfection. But Wagner’s personal life, which gave rise to the Siegfried Idyll, was something else again.

The Siegfried Idyll takes its name from Wagner’s son by his second wife, Cosima. At the time they fell passionately in love, Cosima — who was Franz Liszt’s illegitimate daughter by the glamorous Parisian socialite Marie d’Agoult — was married to the distinguished conductor Hans von Bülow, one of Wagner’s strongest supporters. Beset by financial and artistic turmoil, Wagner accepted the Bülows’ offer of refuge in their country house in Tribschen, near Lake Lucerne.

Richard Wagner

Wagner’s affair with Cosima von Bülow was just one of many on his part, but it proved fateful, finally dooming his marriage to his first wife, Minna. Wagner felt that his genius and his passion were reasons enough for his host and former pupil to step aside; inflamed by love, he was inspired to begin work on his revolutionary opera Tristan und Isolde. For her part, Cosima became pregnant with their daughter Isolde. When Minna conveniently died in 1866, Cosima’s husband granted her a divorce, and she and Wagner married. Two more children followed: Eva and Siegfried.

When Cosima entered Wagner’s life, it was as if they were transfigured beings who entered the world of Wagner’s creative imagination. Their shared passion crystallized for Wagner the premise of Tristan und Isolde — the transcendence of inner, spiritual love over external reality and human law — and their relationship unleashed his work on his most innovative music. Together, Wagner and Cosima embodied not only the creative fantasies of his music dramas, but also the principles of his writing on aesthetic philosophy, including his insistence on the purity of German art and myth, and his virulent anti-Semitism. Cosima furthered these ideas after Wagner’s death, managing the opera house at Bayreuth as a shrine to her husband and his ideas.

Though it is relatively short (for Wagner) and intimately scaled for a chamber ensemble, the Siegfried Idyll is in a sense a token of this special moment in the life of one of music history’s most remarkable and disturbing figures. Composed in appreciation of the marital joy that Wagner and Cosima enjoyed after his years of turmoil, it was conceived as a gift for Cosima and specifically scored for an orchestra of 13 to 15 players to be positioned on the stairway leading to Cosima’s bedroom. It was rehearsed in secret and played to awaken her on Christmas Day in 1870.

Originally titled the Tribschen Idyll, the Siegfried Idyll is ecstatic and flowing; like so much of Wagner’s music, it seems to nullify the external sense of time with its own timeless pulse. It begins with a sunrise both literal and figurative, a beautiful dawn that also marks the beginning of a new kind of life. (The work’s original subtitle indicates that the sunrise is orange, and that a bird, “Fidi,” is singing; both the roseate tones of the morning sky and the poetic birdsong are evident in the music.

As a kind of gift card to supplement the Idyll, Wagner provided a poetic dedication to Cosima in which he explained the work as follows:

It was your self-sacrificing, noble will

That found a place for my work to develop,

Consecrated by you as a refuge from the world,

Where my work grew and mightily arose,

A hero’s world magically became an idyll for us,

An age-old distance became a familiar homeland.

Then a call happily rang forth into my melodies;

“A son is there!” —he had to be named Siegfried.For him and you I had to express thanks in music—

What lovelier reward could there be for deeds of love?

We nurtured within the bounds of our home

The quiet joy, that here became sound.

To those who proved ever faithful to us,

Kind to Siegfried, and friendly to our son,

With your blessing, may that which we formerly enjoyed

As sounding happiness now be offered.

The Idyll can be heard as an attempt to transmute infidelity into nobility, like lead into gold. The morality may be questionable, but it is difficult to argue with the beauty of the music.